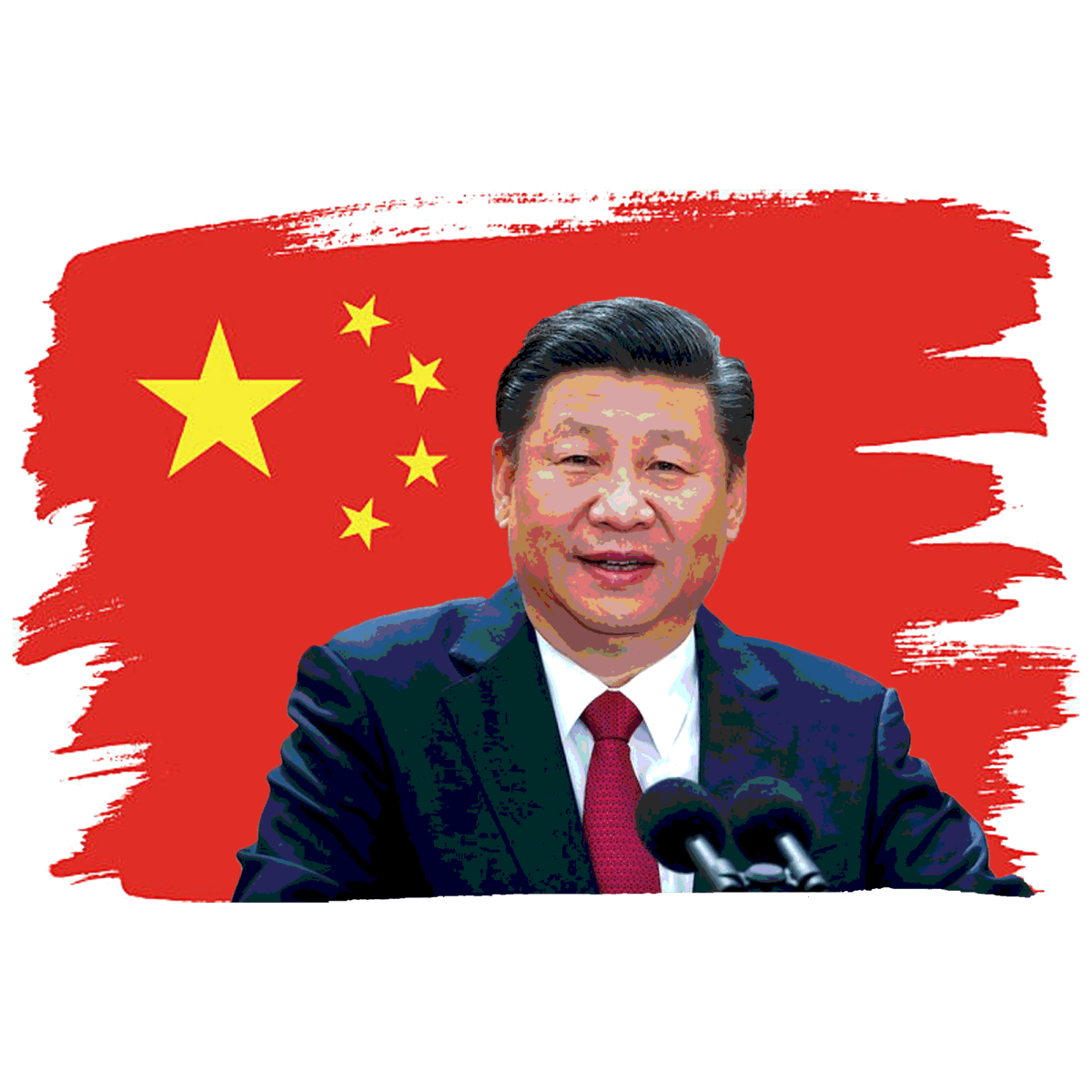

In March this year, China’s National People’s Congress voted to abolish presidential term limits, paving the way for President Xi Jinping to remain indefinitely in office. The move marked a radical change from China’s norm-bound system of leadership succession, raising questions about the survival of the current regime. Yet far from exposing the regime to the chaotic power struggles of the past, the move marks a logical step in Xi’s consolidation of power and the worrying resurgence of the personalistic dictatorship.

In the 1980s, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China began to implement a range of reforms aimed at ensuring stability in the post-Mao era. A set of clearly defined rules for leadership succession, including the requirement to retire at 70 and a two-term limit for the presidency paved the way for smooth, non-violent leadership transitions. With the chaotic power struggles of Mao’s era out of the way, China welcomed a new era of stability – one supposedly resilient to the emergence of yet another personalistic dictatorship. It wouldn’t last.

So what went wrong? In 2002, Jiang Zemin peacefully transferred his leadership position to Hu Jintao, with the same stable transition occurring between Hu and Xi Jinping in 2012. Yet the removal of the two-two limit marks a radical, although anticipated, shift in the system. With the two-term limit removed, Xi will not be required to step down as president in 2023 – once his second five-year-term is up. This major change has likely ended any remaining hopes for democratisation in the world’s fastest growing economy. Yet more than that, it has exposed – with clarity – Xi Jinping’s intentions to position himself as China’s next leader for life.

It is this cult of personality that draws comparisons to Mao. And the removal of term limits is not the only change that suggests this. The 19th Party Congress confirmed “Xi Jinping Thought” as the central political doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party (the CCP). This move has propelled China into a new era of politics, one that is shaped by the ideas of one man – Xi. As Chris Buckley of the New York Times argues, the doctrine serves as a blueprint for Xi’s consolidating of power at the national, party, and personal level. It makes sense, in this context, for Xi to remain on as leader indefinitely – after all, the future of the CCP is now completely intertwined with Xi himself.

It is changes like these that have commentators worried about the direction China’s future is moving towards. For the last six years, China has been creeping slowly towards a dangerous form of authoritarian nationalism. The move to abolishing presidential term limits fits in with this trend, marking the natural end point of increasing state antagonism to Western democracy, persistent and invasive censorship, and increased crackdowns on civil society.

In politics, nothing is inevitable. Yet Xi’s removal of two-term limits came close to it. But it would be naive to suggest that the country is edging towards a personalistic dictatorship much like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, or Kim Jong-un’s North Korea. Rather, Xi Jinping has positioned himself as the personal driver of growth and prosperity for China’s future, with citizens reaping the benefits. His consolidation of power is worrying – but with China’s current economic might on the world stage, and high levels of support for the current regime, it doesn’t appear as though the CCP will lose its grip on power anytime soon.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.