CW: Violence, Racism

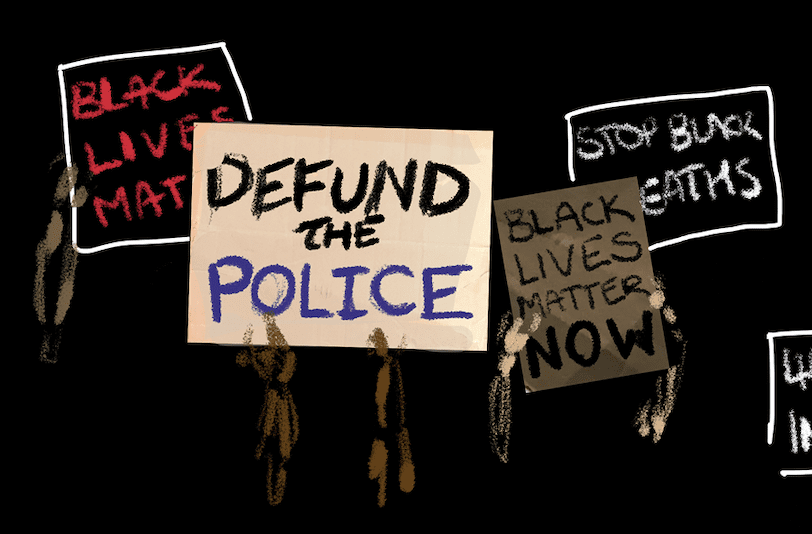

Before 2020 began, DEFUND THE POLICE was largely considered a statement too radical to grace the stages of public discourse. After all, no one alive today can remember a time without law enforcement and prison. We take the police for granted because we’ve been taught that this system is the only way to protect us from ourselves. The ongoing international Black Lives Matter movement, however, is proving that for racial minorities, especially black people, the police more readily shoot than serve. The movement calls for an exposure of the police’s systematic flaws that may only be remedied by a complete deconstruction of the institution.

The switch has been flicked, the white fluorescents turned on, and law enforcement has been forced to take its seat in the interrogation room. How do you explain the police’s institutionalised racism? Why are officers so seldomly punished for cases of brutality? What purpose does this corrupt system serve in today’s communities? These questions, previously lurking in the shadowy corners of ‘radical’ politics, have been illuminated. Audiences who might have automatically dismissed the idea of police abolition (defunding’s parent ideology, and one closely linked in aim) are beginning to realise this trick of the light may have more substance than initially believed.

Discussions of defunding and abolition are not new. For decades, activists have asked: why do we accept the human rights abuses – assault, degradation of human life – that blatantly occur at the hands of police, disproportionately to minorities? Certainly, vigorous and harsh policing is as expected in our society as high school and supermarkets and considered by many to be just as necessary. Advocates for police abolition, however, question the necessity of such systems in our current setting. American activists such as Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore have written extensively on the haunting evolution of the modern police force from the patrols who hunted down the criminals of the 18th and 19th century – escaped slaves. If we’ve abolished slavery, why do we still rely on a similar system of policing? Abolitionists believe today’s law enforcement has been allowed to accumulate more power than our social setting should allow, that it serves not only as a first responder but also as judge, jury and – in all too many cases – executioner.

At this point it might be worth clarifying that abolitionists and defunding advocates aren’t just erratically waving flashlights in people’s eyes calling for Purge-esque anarchy. The abolition movement recognizes the necessity of force to apprehend actively dangerous people. However, they identify the institution that has repeatedly killed unarmed or detained people as severely flawed. They understand these flaws as being inherent to its very structure, and therefore the only way to address them is by complete dismantlement. Over-weaponization and unreliable punishment systems have been cited as the primary enablers of police violence. If defunded, law enforcement would need to rely on peaceful de-escalation tactics as opposed to suppressive weapons. Police abolitionists support this reconstruction, a process that can only be effectively kick-started by reducing the funds, and therefore the power, that permits the police to commit acts of brutality.

Although yet to receive the same international scrutiny as the United States, Australia is far from innocent of police violence. Prejudices against Indigenous Australians and racial profiling in the Australian police force often lead to escalation when interacting with Indigenous Australians, resulting in a detention rate disproportionately affecting this group. Indigenous Australians are one of the most incarcerated demographics in the world, making up 27% of Australian inmates while comprising only 2% of the national population in 2018. Debbie Kilroy, a lawyer working for and with incarcerated women, wrote:

“Prisons have ravaged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities… Pipelined from out-of-home ‘care’ to youth prisons to homelessness, poverty and adult prisons, women and girls are trapped in a cycle of government failure.”

The inability of the Australian government and police to understand and address the underlying causes of crime in Indigenous communities – systematic racism, generational health and poverty issues – means incarceration rates continue to grow, and with them, rates of state-sanctioned violence against Indigenous Australians. Since the 1991 Royal Commission into Indigenous deaths in custody, over 430 Indigenous people have died while imprisoned. No officers or prison staff have been convicted for these deaths.

The current Black Lives Matter movement is ensuring that these injustices no longer have a dark corner to hide in. Increasingly, the idea of police as inalienable is being questioned. The anger of marginalised groups targeted by the police has become too potent for gradual reformist policies to be widely satisfactory. Who do these policies benefit? More importantly: who don’t they benefit? By example, mandatory bodycam usage is a consequential policy – it requires the brutality to already have occurred for the footage to be useful, at which point someone’s parent, sibling or child has lost their life. Policies aimed at gradual reformation are often treatment of symptoms, not prevention of the problem embedded in the very origin of the police. It is the latter that the abolitionist and defunding movement is aimed at.

DEFUND THE POLICE calls for governments to stop financing a broken system and redirect funds into community education, social services, drug and mental health rehabilitation, and to cease incarceration for nonviolent crimes such as unpaid fines. Police abolition proposes replacing a large percentage of police officers with health and social workers more capable of recognising and mitigating the underlying causes of a triple zero call. For these changes to occur, abolitionists propose we must 1) reveal police crimes through movements like Black Lives Matter, and 2) reduce the power of the current outdated institution, a process that starts with defunding.

Thrust under the interrogative fluorescents, the structural flaws of law enforcement become clearer each day. The institutional failure to serve and protect marginalised groups can no longer be ignored. The police claim to be the purveyors of justice, but for their own crimes, abolition may be the only punishment severe enough.

Think your name would look good in print? Woroni is always open for submissions. Email write@woroni.com.au with a pitch or draft. You can find more info on submitting here.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.