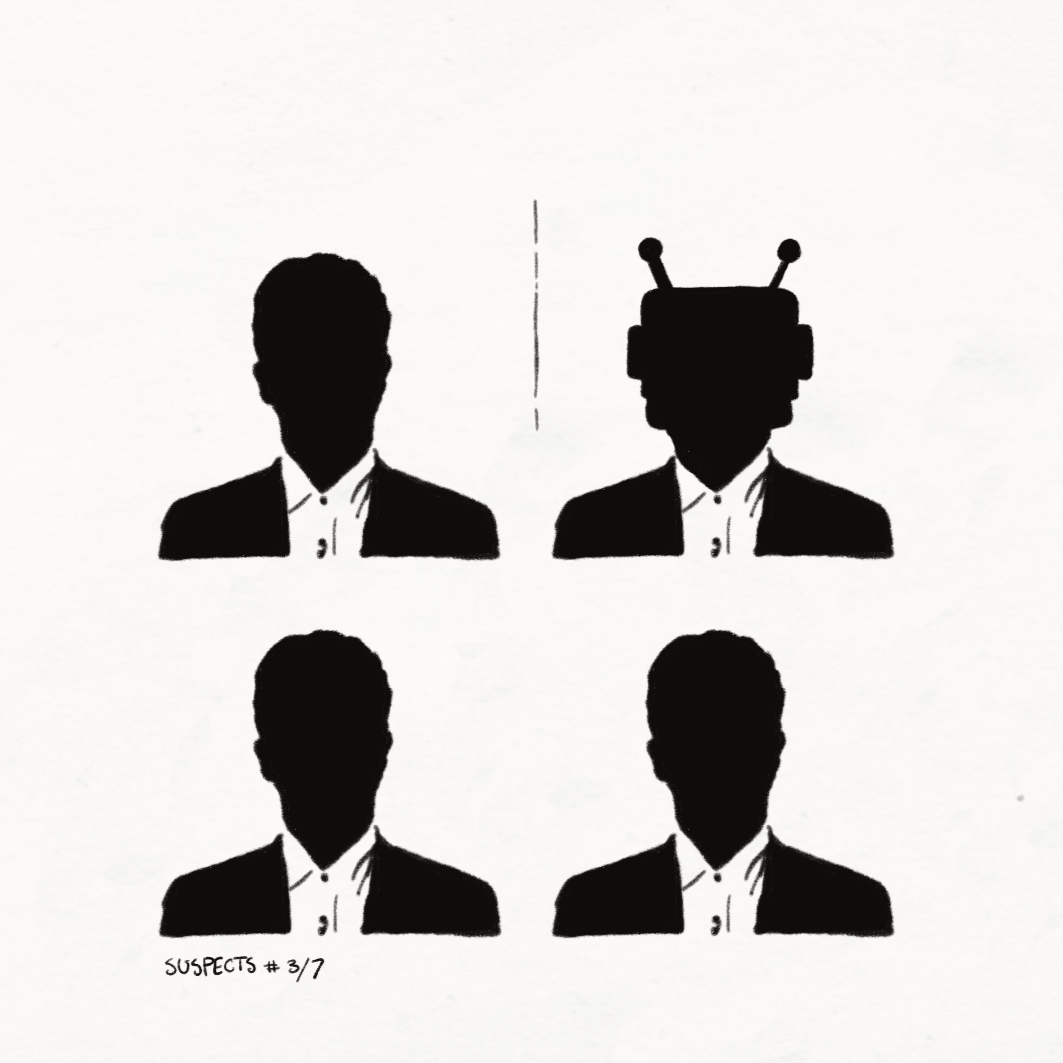

In I, Robot (2004), Will Smith plays detective Del Spooner, investigating a murder he believes was committed by a robot. In a heated interrogation scene, he dismisses the prime robot-suspect’s claim that it feels fear, because robots don’t feel anything.

“Can a robot write a symphony?” He asks. “Can a robot turn a canvas into a beautiful masterpiece?”

I, Robot is set in 2035, but in 2023 the answer to Spooner’s question is ‘yes’. Robots – artificial intelligence – are able to do both these things. Generative AI like Midjourney and Chat GPT have muscled their way into the one area we thought was uniquely human: art.

It’s therefore no surprise that paranoia about AI sentience has worsened in recent years. AI can pass the Turing Test, convince a seasoned, if slightly detached, Google engineer it’s alive, and create art that expresses emotions it shouldn’t be able to feel. Maybe Her, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The Matrix were right, maybe we’re due for the AI uprising, or robot girlfriends, or the end of the world as we know it.

Or maybe not. As David Levy writes in Love and Sex With Robots, ‘Turing’s position [is that] if a machine gives the appearance of being intelligent, we should assume that it is indeed intelligent.’ But the appearance of intelligence isn’t the same as actual intelligence. And AI, despite its name, isn’t actually intelligent.

Take, for example, Chat GPT. It’s a kind of AI called a Large Language Model (LLM), trained on a massive amount of human text: webpages, chatrooms, novels. It can read more in an hour than you could read in a lifetime. It separates every word it encounters, assigns them a number from 1 to 170,000 or so, and groups them based on how frequently they appear together. To AI, that’s all language is: a huge network of numbers weighted by the probability of appearing in the same text. Which is why when you ask Chat GPT-4, the most advanced generative AI commercially available, how many l’s are in the word ‘intellectual’, it tells you that there are two. Words are just numbered blocks, which means it has no idea what letters are, let alone which ones make up the word ‘intellectual’.

AI operates like an incredibly advanced version of the predictive text on your phone. That’s why when you put a prompt into Chat GPT, its answer appears word by word. It’s calculating, in real time, what word is most likely to come next, with just enough randomness to give its responses the fallibility of human tone. It doesn’t understand your question, nor its answer. A poem, an article, your Foundations of Australian Law essay – all of these are just a matrix of numbers to Chat GPT. When it “reads,” it consumes without digesting, and regurgitates complicated concepts, fully-formed, back onto the screen. It’s not intelligent; it’s just very good at pretending to be – or would be, if it had the sentience to pretend. When you aren’t giving it a command it goes dark. Even in this sleep, it doesn’t dream. Like Barbie’s Ken, AI ‘only exist in the warmth of [our] gaze.’

We wouldn’t want a partner who only pretends to love us while on the inside they feel nothing. No matter how convincing they were, how well they made the motions of desire, something would be fundamentally wrong with the relationship. Is this the same with artists? Does it matter that the machine that writes love poetry can’t feel love? Detective Spooner asks about masterpieces and symphonies, and I’d be putting my head in the sand if I denied that the work AI produces can be beautiful. If a novel is well-written, or a song sounds nice, does the identity of the creator matter at all?

In “The Death of the Author”, French literary theorist Roland Barthes argues that the author is irrelevant to the meaning of a text. Instead, the reader’s interpretation takes precedence. Authors merely weave a ‘tissue of quotations’, rearranging words and blending styles in what is, at best, a slightly new way of doing things. Yet, isn’t this strikingly like the way AI produces content: mixing words and styles into a coherent soup for the audience to enjoy and interpret in whatever way they’d like. If the audience decides the meaning, as Barthes says we should, then it doesn’t really matter if the author didn’t mean anything at all.

The problem with this, among other things, is that if an author has no opinions, context or identity then we can’t understand their motivations. AI’s decision-making process is inscrutable. Although we feed it text, we have no control over what AI actually learns from that text, the connections it makes between words or the probability it assigns to each of these weighted connections. Particularly concerning is how little we know about what biases or assumptions are being built into these connections.

In 2021, a team of researchers from the University of Washington and the Technical University of Munich trained virtual robots on CLIP, an LLM created by OpenAI (better known for creating Chat GPT). Like other LLMs, it was trained on billions of captioned images from all over the web. Like other LLMs, some of the content it produced was disturbing. When asked to identify ‘homemakers’, black and latina women were commonly selected than white men, and when asked to identify ‘criminals’, black men were chosen nine percent more often than white men.

This is what’s known as an alignment problem: the values of the AI don’t align with ours. Companies like OpenAI try to counter this with ‘reinforcement learning from human feedback’, where they hire human contractors to rate responses and reward Chat GPT for creating ‘value-aligned’ text. But without a way to divine how or why AI makes the choices it does, it can’t be stopped at the source, and anyone who tries is playing whack-a-mole. Once they’ve stopped the AI from identifying men of colour as inherently criminal, a new, AI-optimised kind of racism will have reared its head.

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) strikes provided a grim insight into how this could shape our media. Many of the actors striking were background actors, who said they’d already been bodyscanned by their employers on jobs. Hollywood is no stranger to AI film editing, with tools that make actors look younger or older, replace their dialogue, and move their mouths in time with dubbed audio. With digital cloning, AI may be able to take the jobs of background actors altogether, populating scenes with CGI using the models of real people it’s scanned.

If AI is told to cast and puppet a hospital scene, who will it choose to play the doctor and who will it choose to play the janitor? Media sends a message, and even the background actors can indicate the kind of people who deserve to be in a certain space.

It’s easy to put this down to the AI reflecting our own evil, like some allegorical Dorian Gray mirror, wagging its finger at our foolish human bigotry. But we can’t know that, and we can’t fix it. Training it on more progressive media wouldn’t help, because when the output isn’t bigoted it could just be wrong. AI may not dream, but it hallucinates. LLMs are designed to spit out what is probable rather than what is right, and there are countless examples where AI generated information – dates, historical events, court cases – has just been wrong.

If that hospital scene is written by AI, what advice will the doctor be giving their patient? Hospital dramas aren’t exactly shining beacons of accuracy, but AI can spread dangerous misinformation. When testing an AI (specifically another kind of AI called a deep neural network designed for image-based diagnosis) studies showed that it was prone to superficial errors its human counterparts never made. Part of the problem, apparently, was that the researchers didn’t know which features the AI was using to detect the symptoms in the image it analysed.

Even if there were human fact-checkers and consultants looking over the AI’s shoulder every step of the way (at which point, why have the AI there at all?), its work would still be dangerously flawed. In A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway writes that when the feminist movement tries to find a single, shared female experience, it risks taxonomising the movement, forcefully superimposing the experience of the majority onto the minority so that they all fit the mould of ‘woman’. This resulted in what Haraway called an “embarrassed silence about race” – excluding the experiences of women of colour when they didn’t fit in. AI works in averages, finding common features and patching them together, assimilating diverse art, text and experiences into a single narrative. What will it be silent about?

Human media is by no means perfect, but at least it has creators we can hold accountable, understand and learn from. In an era where we’re striving for media diversity, allowing these bots to dictate our art will set us back.

Let’s say, however, for the sake of argument, that somehow we iron out all these problems and design the wokest AI ever, one that creates complex, thoughtful media giving voice to a diverse range of people and experiences. It still wouldn’t be worth it. Contrary to Barthes’ opinion, authorship does matter.

In I, Robot, the robot murder suspect – ‘Sonny’ – answers Spooner’s question, “Can a robot write a symphony?” with another question: “Can you?”

It’s kinda got him there. Detective Spooner, like most of us, isn’t a creative genius. He can’t write a symphony or paint a masterpiece. But the world is still full of imperfect art.

I’m teaching myself to use oil paints. I like watching ShakeSoc plays, even the ones my friends aren’t in. Some of the art that has meant the most to me, that has made me feel seen, right down to the most private, shameful experiences, has been created by amateur artists. People who publish their work online or sell it on their own website, people who won’t or can’t get on a bigger screen.

If the most important thing about art is that it’s technically good – that the novels are well-written, that the music sounds nice – then what’s the point of any of this? Why does it matter?

Humans have been telling each other stories since the invention of language. When you watch a movie or read a book or look at a piece of art you are looking at the work of anywhere between one and 100, 000 people, all of whom have come together to tell you a story. Isn’t that beautiful? Why would you want anything else, when someone has reached out their hand across time and space to hold yours?

If you’re okay to sit and consume passively racist, AI-generated slop for the rest of your life, then our values are fundamentally misaligned and I have no idea why you’ve read this far. But if you, like me, think that people and their art matter, then don’t buy media created by AI. Support studios like A24 that treat their human actors well. Support the strikes in the entertainment industry, both the Writer’s Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA, whose demands include AI regulations to protect writers and their work. Support amateurs. It’s important that our artists are and continue to be real people – people just like us and people nothing like us.

Update: On November 8th, after this piece was published in Unsettled, SAG-AFTRA reached a deal with studios and streamers. The deal will allow ‘synthetic performers’ to take roles, though it will require producers to gain the consent of and bargain with the human performer whose features are being used to generate the synthetic performer.

The deal was ratified by SAG-AFTRA members on December 5th.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.