In the last decade, anyone from box office devotee to casual content consumer would have noted a significant uptick in media featuring a multi-universal plotline. At face value, it’s difficult to ignore the clear corporate motive behind a cheap plot device which employs pseudo-quantum physics to revive retired characters and stories for nostalgic fan service. Half of the current Marvel suite immediately springs to mind – What If…?, Shang-Chi, Spider-Man: No Way Home, Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness, in that order – but there’s also Riverdale, The Good Place, and Supernatural, to name a few.

Yet the more recent (and arguably, more philosophically stimulating) phenomenon is the use of the multiverse concept in the kinds of media that makes Letterboxd users foam at the mouth: Into and Across the Spider-Verse, Rick and Morty and perhaps most prolifically, and most deliciously zeitgeist-y, in last year’s Oscar-winning Best Picture: Everything, Everywhere, All at Once. Everything, Everywhere is directors’ Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s delightful maximalist genre-bender, which manages to instrumentalise butt plugs and hot dog finger universes with a cool, Saganist flair (for devotees of astronomer-astrophysicist-philosopher Carl Sagan, his own daughter pens an essay in the coffee table book accompaniment to the film, available on the A24 website for a neat $52 USD). The tone of these flicks, tangentially, can also be seen as somewhat antidotal to their non-multiversal but similarly-themed media cousins, which feature prominent characters grappling with nihilism: Bo Burnham’s Inside, Season 2 of Fleabag, Bojack Horseman.

Evelyn’s revelation at the end of Everything, Everywhere is that because nothing matters on a cosmic scale, everything matters – the minutiae of our everyday lives, the care and regard with which we hold our family, our chosen family, our community. Because nothing matters, the only things that matter do so because we imbue them with meaning. The realisation of a lack of inherent meaning can either be terrifying, as it is for Joy, or liberating, as Evelyn comes to learn.

In Everything, Everywhere’s case, the multiverse plot device and its premise of alternative lives branching out from our individual decisions – to stay or to leave – appears impeccably well-suited to tell the immigrant story of risk, sacrifice and precarity, where singular choices form delicate negotiations with the greater good of a family. But beyond this, the tightrope-fine walk between nihilist defeatism and existentialist liberation which the film’s multiverse concept allows has become iconically emblematic of the outlook of Generation Z, packaged so neatly in our affinity for meta-ironic humour.

I was born in the first week of September 2001, at 0.6 degrees warming. My generation has grown up in the shadow of enough world-altering events to create a perfect collision between a terrifying reckoning with our ultimate powerlessness and liberal messaging around individual responsibility, for both our own social mobility and universal challenges. There is a kind of paralysis that comes from individualism as a culture and practice, which is at odds with a growing need to locate responsibility for large-scale issues in institutional homes (eg. corporate, colonial, and otherwise structural culpability for climate change).

It’s comforting, given the scale of our reality and our problems, to simultaneously contemplate both one’s cosmic insignificance and self-importance. It allows us to hold the contradictory beliefs that our small bad actions don’t matter in the grand scheme of things (using a plastic straw, being mean to a sibling) while our small good actions (recycling, reposting an Instagram infographic) do matter – all at the same time. It allows us to experience being inconsequential without having to actually endure the death of our egos – ostensibly our final personal commodities as we move our interactions online.

It’s comforting, in the age of the multiverse, to think that alternative versions of you could be out there, providing some form of cosmic guidance. Peter II and Peter III are there in the end to stop Peter I from making the same mistakes. It’s comforting to think that in another life, things could be far worse. In Evelyn’s universe, she’s definitively living the worst version of herself. It’s comforting, potentially guilt-assuaging, to think that in another life, just a few different choices or opportunities away, maybe you could have got it right – maybe we all could have got it right.

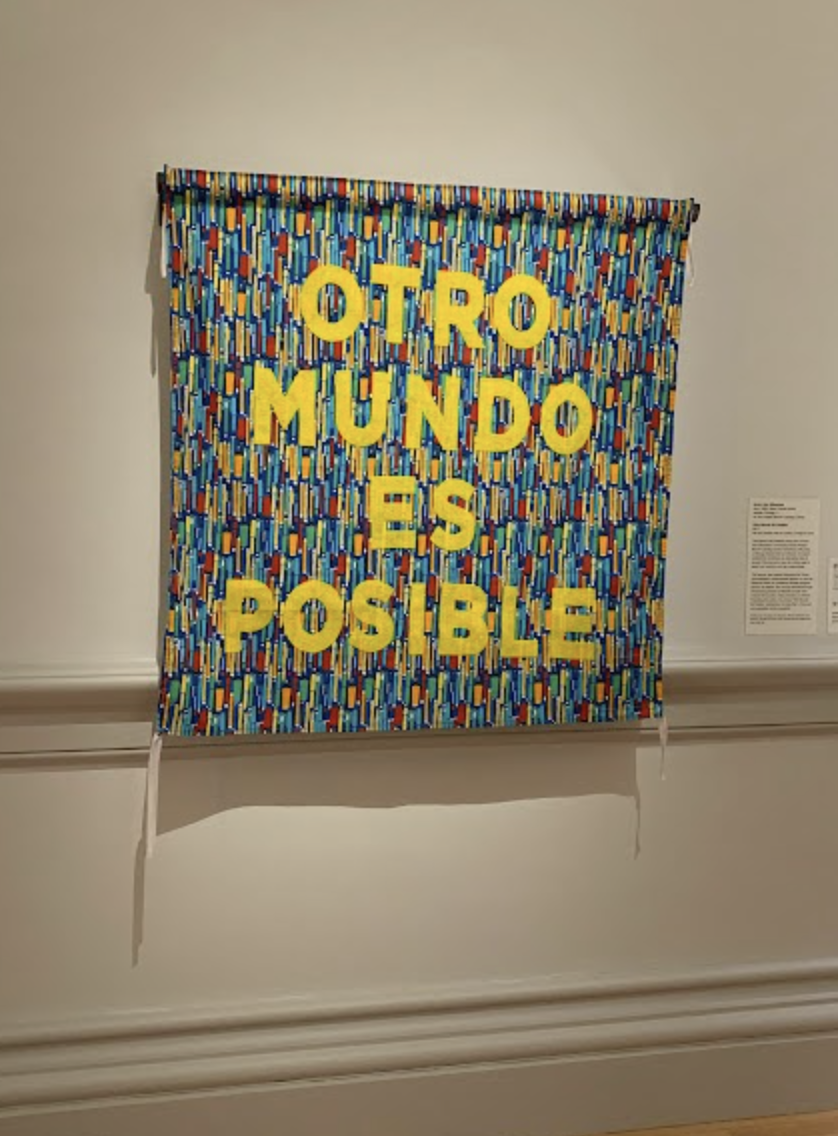

But these kinds of notions hold meaning with a tenuous grip. I am worried that if we find enough comfort in the prospect of alternative realities where, simultaneously, things are both better and worse, then we can consciously or subconsciously become complacent in what we have in our own, which is perhaps the only real thing we have. It’s easier to imagine a different reality than to figure out how to make ours liveable – just as it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. At some point, the escapism provided by the prospect of alternate worlds absolves us of the responsibility to consider what our own world would look like if we could make it better, and therefore the ability to believe wholeheartedly that we can.

I’m no progressivism truther, and I am inclined to believe nobody has a right to tell anyone how to struggle in this life. But I also believe that hope, in the post-Obama sense, is an important ingredient in all movements – that the process of creating a world that we believe wholeheartedly is worth saving, is a necessary prerequisite to saving it.

We have to land somewhere in the middle, beyond both the failed promise of individual mobility and inherent meaning, and the despair of giving in to our cosmic insignificance. Somewhere more favourable than resorting to fictional alternate media universes just to alleviate the weight of our inevitable destruction. Theistic beliefs aside, what if we were to operate like we all matter to each other, like each person’s flourishing is our collective flourishing, like our planet matters because it allows that flourishing to happen? Like we made this meaning, we pulled it out of our arse, but that’s the best part. It means that nothing matters, other than what we decide does.

Our fixation on multiverse media speaks to a generation’s collective wound, which looks not coincidentally like a bagel. It speaks, I think, to a need to rediscover and operate from a politic of love, a politic that enables us to reckon with the meaning, good and bad, of our individual choices and actions – particularly for those of us who belong to the group which hold a disproportionate portion of global structural power. A politic which compels us to better our communities and our world, not as a project of individual responsibility or self-actualisation, but because if nothing matters, all that matters is what we say we have, here and now, in each other.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.