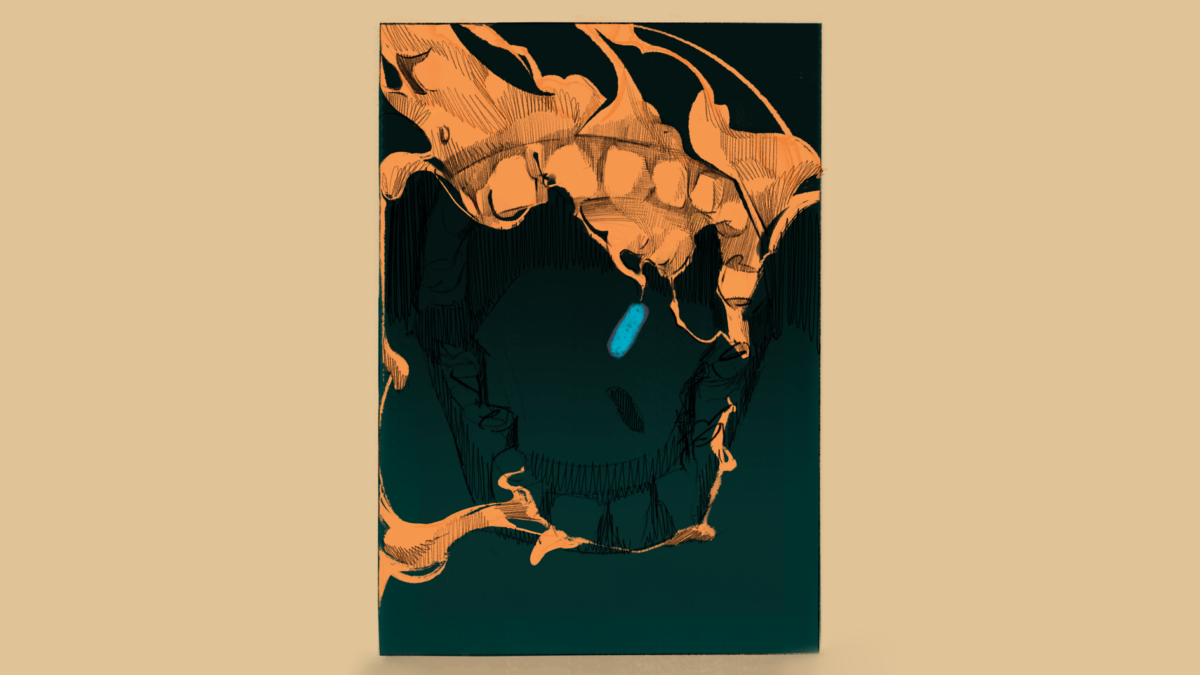

After my cleanser, cologne, and a hasty rummage through my wardrobe to assemble an outfit, my daily morning routine concludes with a cerulean pill.

At 7:20 AM, an appointment time fixed by an unsnoozable alarm, I swallow a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate — a mouthful of a name belonging to a single, light-blue tablet. This daily regimen constitutes a form of preventive therapy called Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, or ‘PrEP’ for short; I take medication that protects my cells from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), lowering the risk of me, an HIV-negative individual, contracting the virus from a potentially HIV-positive partner by upwards of 99%. If someone not taking PrEP gets exposed to HIV for up to 72 hours after the suspected exposure, the same medication can be taken as post-exposure prophylaxis (‘PEP’) and similarly obviate infection (analogous, in a way, to emergency contraception). Since April 2018, the Australian government has subsidised PrEP via the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, a monthly dosage costing $30 for thirty pills. At first, I complained about the cost of taking PrEP daily. In my foggy bathroom mirror, I saw myself as some profligate piggy bank who swallows a dollar each morning with a swig of tepid tap water.

One evening, after begrudgingly picking up a month’s worth of PrEP from the pharmacy, I passed a man wearing a Keith Haring sweatshirt. I vaguely knew of Haring, his art, and his story; he was one of many gay artists whose work I admire and aspire to one day honour, along with the likes of Oscar Wilde, Félix González-Torres, and James Baldwin. That glimpse at Haring’s venerated stick-figure iconography woven into the stranger’s likely sweatshop-produced top piqued an incessant bout of bus-ride research that supplanted the ennui of commute with a vibrant flush of information: the history of community health; the eclipsed world of low-brow queer art; the contrasting responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, a crisis that decimated a generation of ancestors whose short lives I can know only in retrospect through compendia of archival – and often posthumous – accounts.

The virus, which was initially dubbed ‘Gay-Related Immune-Deficiency’ or ‘GRID’, razed gay communities across America. In The AIDS epidemic’s lasting impact on gay men, Dr Dana Rosenfield wrote that by 1995, “one gay man in nine had been diagnosed with AIDS, one in fifteen had died, and 10% of the 1,600,000 men aged 25–44 who identified as gay had died”. As a homophobic Reagan-led government refused to fund the pharmaceutical research and development necessary for identifying the aetiology of these peoples’ illness, a paramilitary force of lesbians and bereaved mothers flocked to gay mens’ need, providing medical treatment for doctorless patients. All of this treatment was palliative, of course. There remains no cure for AIDS, and during the ‘GRID’ crisis, some medical practitioners mocked, neglected, or outright refused to provide care for the emaciated gay people withering away as breathing corpses in visitorless wards. The four letters of ‘GRID’ could just as easily be swapped out, like Scrabble tiles, for ‘G-O-N-E’, ‘D-E-A-D’, or ‘L-O-S-T’.

After befriending a young gay man during a period of immense grief and loneliness, an older straight mother named Mary Jane Rathburn began volunteering at San Francisco General Hospital. Brownie Mary, as she came to be known, illegally baked cannabis-laced brownies for AIDS patients whom she referred to as ‘her kids’. Mary’s unlawful culinary habits led to three arrests, resulting in stints of community service, which she chose to serve by further tending to her infirm children. Mary campaigned for legalising cannabis for medical use, and her activism culminated in two legislative tools, Francisco Proposition P and California Proposition 215, as well as America’s first medical cannabis dispensary. Mary’s nostrum proved to be a much-needed relief for those with little else to remedy their final days on Earth. How many stories, tales, names — how much history and knowledge — have we collectively lost, buried into obscurity with skeletons in graves left unattended by homophobic families?

For every pill I shake out of that bottle, 1.3 million individuals have lost their battles with HIV, often dying young within years or even months of contracting the fatal virus. That said, I am lucky to inaugurate my queer, embodied adulthood here in contemporary Australia, a nation boasting remarkable reductions in HIV diagnoses — some predict a near-total elimination of HIV transmission by 2030! However, regardless of the progress, as grateful as I am, I cannot help but metonymically see my pill bottle as a coffin laden with millions of individuals who lacked access to such a medicinal marvel. Individuals for whom I can not ration my tablets to resurrect their bodies from their graves. I wish I could sprint to my nearest printer and scan thousands and thousands of copies of my prescription to distribute to vulnerable communities with the same communal care as Brownie Mary. I wish I could confer my access to the life-saving medication that, at one point, I had resented for its price. But I can’t.

The tiny blue pills mean much more to me now than I had initially realised. The antiviral compound is squeezed from a mythos of narrative, tragedy, and would-be cultural ancestry belonging to a myriad of half-lived lives. In the face of remiss governments, social stigma, and medical negligence, a fierce brigade of allies and loved ones supplied people living with HIV with makeshift medicine borne from a labour force of love and rogue alchemy. Reflecting upon my daily pharmaceutical consumption and researching PrEP’s predecessors revealed the real pathogen lurking beneath the surface: bigotry. It is a ‘plague-spot’, in Sophocles’ words, that accelerates the progression of public health crises time and time again — be it the sinophobia behind COVID-19 or the anti-Africa racism that followed the Ebola outbreak. Atavistically, I propose a measure for health crises that ravage a specific demographic or community: rather than ostracising those who are the most susceptible to illness and the epistemic plagues of misinformation, dismissal, and ignorance, we ought to return to the grassroots healthcare of Mary Rathburn and follow her recipe of care.

Laced brownies optional.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.