Most of us know that sinking feeling of betrayal when one of our heroes is revealed to be less than the epitome of moral virtue we thought them to be. It’s not uncommon these days, and particularly in the realm of sports the list is growing long quickly. Given the magnitude and regularity of these falls from grace – from Marion Jones to Lance Armstrong – one has to wonder why we even place sports stars up on this pedestal in the first place.

Whilst this phenomenon is not endemic to Australia, idolising sports stars is very much a part of our culture. We do it unthinkingly; it’s a natural progression that goes with the territory. It’s assumed in our cultural DNA that if you’re good at sports then you’re probably a good person. If you doubt this, you need only to go down to the National Museum to see Phar Lap’s encased heart and witness immortalised perfection – and he wasn’t even human! In earning the praise of the public it doesn’t matter which sport you play, so long as you’re good enough.

One might think we pump up sports stars only to watch them spectacularly deflate. Yet the reason why we do it is simple: we love sport, and it’s easy to conflate attributes needed to excel in sport to attributes desirable in life. At face value, the virtues of hard work, self-motivation and overcoming physical and mental hardship should be transferable across disciplines. Striving to be – and actually becoming – the best at a particular thing is a noble pursuit, no question. But attributes are attributes; they can be used for good or ill. As a society we don’t think a hard-working, self-motivated criminal who overcomes physical and mental hardship to commit a crime is worthy of idolisation. Shouldn’t we then be asking ourselves why, for example, a full-time ball-hitter is necessarily a good role model for our kids?

This is not to argue that sports stars cannot be role models – and of course, they shouldn’t break the law. My point is that we shouldn’t automatically assign them to the ‘role model’ category. Instead of having to worry about modelling good behaviour, sports stars should model the exemplary sporting skills for which they have actually trained.

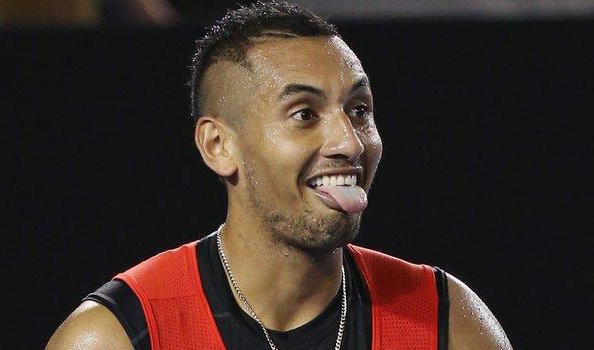

And here we arrive at Nick Kyrgios. If you’ve made it this far, I hope to have already convinced you that we shouldn’t be idolising him. If you’re in the majority of haters then you probably agree. Yet the damage caused by this ill-placed moral expectation has already been done: we’ve already thrown this young man under the bus. And I use the word ‘we’ deliberately here as opposed to just ‘the media’, ‘trolls’, or ‘Dawn Fraser’. The standard we allow is the standard we all accept. We have slandered this prodigious tennis talent 10 times more egregiously than anything he has ever said or done on the court. And this is the other point about Kyrgios: all his antics have occurred on court. Unlike Bernard Tomic’s Lamborghini joyriding down Cavill Avenue or his late night partying in Miami, Kyrgios is hated and shamed for moments of passion and inexperience which occur on court in the heat of the moment.

Why is it that we can’t show empathy and attempt to forgive Kyrgios’ teenage petulance and youthful arrogance? Recently SMH journalist Malcolm Knox declared he wasn’t remotely ‘interested in tennis’ whilst simultaneously jumping on the bandwagon to attack Kyrgios’ character, labelling him a ‘dickhead … uneducated, precociously spoilt [and] insulated from the real world’. The hysteria that Kyrgios whips up in some people is astounding: Knox went on to shame all Australians who might dare to support Kyrgios, especially if he won the upcoming Davis Cup match against the USA (he did). It is bad enough having Dawn Fraser telling you to go back to where your parents came from. But shaming the Australian public for considering the act of forgiving juvenile behaviour is not only ironic but disgraceful.

The hypocrisy of expecting a 21-year-old kid to be a role model for our society only to abuse him when he fails to meet that expectation is absurd. It’s also an outrageous outsourcing of moral responsibility. The boy needs guidance, yet we expected him to guide us. In today’s professional world of tennis, if you aren’t given a racket as you come out of the womb and serving an ace before you say the word ‘deuce’ you simply aren’t going to make it as a tennis professional. Kyrgios trained here in Canberra at the Australian Institute of Sport. He trained to play tennis – he wasn’t in the seminary training to be a monk or attending etiquette classes at a June Dally-Watkins school. He’s a young man whose life is playing out in public, and surely we should give him a break.

This outrage towards sports stars wouldn’t occur if we didn’t expect them to be role models in the first place. Nick Kyrgios signed up to play tennis, and tennis he does unbelievably well. He didn’t seek or choose to become a beacon of moral and social standing and nor should he have to be. I get that we love sport, but can’t we just accept that a good tennis player isn’t necessarily going to be a good role model for our children? Perhaps we need to resurrect villains in sport like in the days of the now-revered John McEnroe, where spectators would build up a villain as a theatrical device without judging whether they were a bad person.

What this whole debate reveals is that we aren’t sure which groups of people we should idolise today. With religious institutions distrusted, politicians loathed and memberships to clubs on the wane, sport stars are easy targets in a shrinking field. Surely, though, we can look a bit harder. There are many fabulous role models in our society doing worthwhile things that we should do more to recognise and praise. Because until we find a replacement category, sports stars will likely remain on this unsuitable pedestal.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.