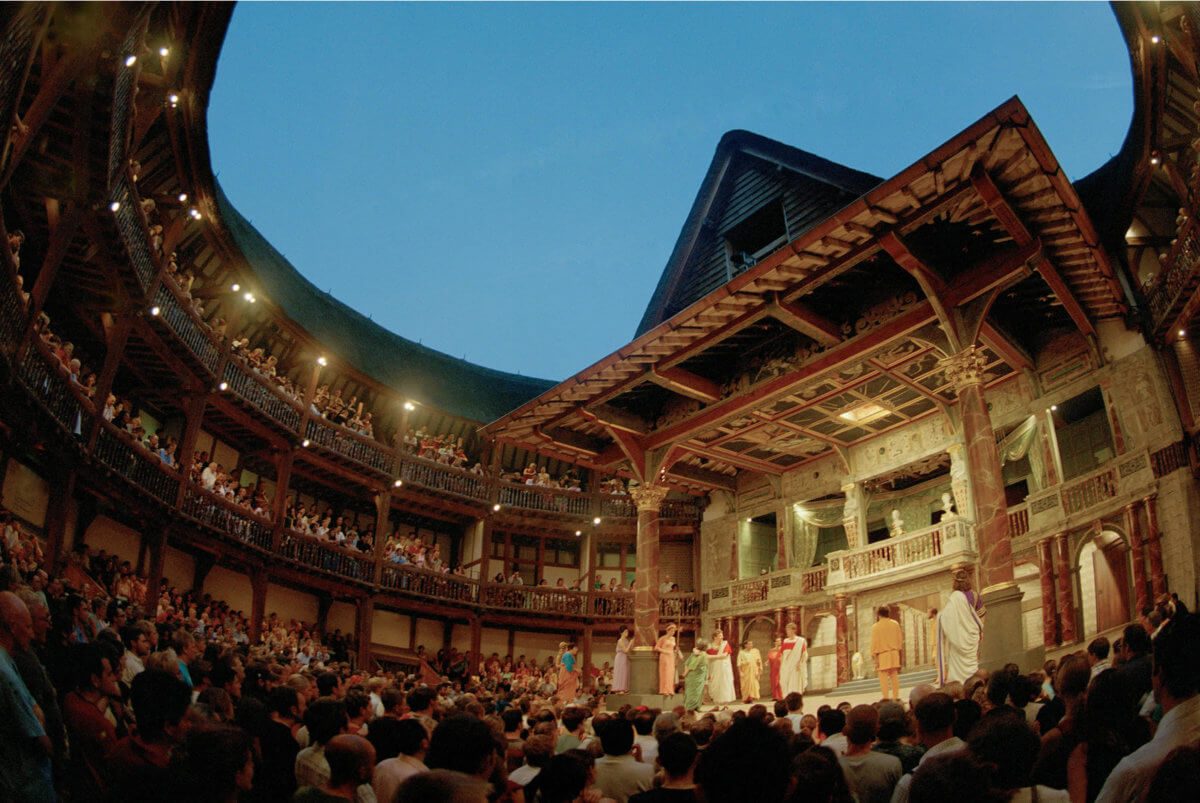

When it was announced that a pop-up recreation of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre was to be opened for performances this year in Melbourne, I immediately started making travel plans. Seeing my favourite plays in the environment they were written for was an event not to be missed. Unfortunately, a quick check of my bank account ended that idea. Even the standing room of the theatre was just too pricey for me.

Many will groan at the thought of sitting (or standing) through a Shakespearian performance: such a ‘highbrow’ expensive exercise isn’t for everyone. But back in his day, Shakespeare was incredibly popular across all levels of society. Going to see one of his plays was as enjoyable as your Netflix subscription. In fact, going to any live performance was pretty inexpensive. So why is viewing a play like Twelfth Night (essentially just a story about a love triangle, cross-dressing and innuendo) so expensive nowadays?

It comes down to the accessibility of the arts, and also what we think of as art. When we think of the arts we tend to think of live theatre, art, dance and live music. These ‘high culture’ activities dominate the creative industries because they’re commercially successful. Unfortunately, they’re successful because they usually cost a lot to access, in comparison to other forms of entertainment. Although this mainly comes from the practical need to cover the costs of live performance, classifying the arts as activities that are largely inaccessible and abstract is a mistake, which contributes to general indifference towards the creative fields.

Art is not just the book of poetry a teacher reads out to a class: it is a malleable, creative medium used to convey a message. This is why art can be a protest or a commentary, challenging or entertaining, or simply a thing of beauty. And context is so important in discerning the meaning; while the artist uses their own ideas to create work, the context that work is accessed in may enable reinterpretation and allow new meaning. Art has the ability to generate different meanings and experiences for each individual, and also exposes us to different perspectives. For instance, Shakespeare’s Richard II has on different occasions been viewed as a historical account, political propaganda, a call to arms and simply a piece of entertainment.

Art is not just the domain of the elite, nor is it limited to the abstract. It is no accident that the most famous plays, songs and artworks are the ones which are relatable, meaningful or iconic. But importantly, the most famous artistic works are those which are widely accessible.

Many perceive the arts as inaccessible because if of the misconception that it is simply ‘high culture’. High culture activities are expensive, clustered around the inner cities and shrouded in traditions and social customs. But the arts are an umbrella under which creativity shelters, and expression is unlimited. Creativity is not confined to the galleries, opera houses and theatres: it lives in the imagination, appears in the house, at the shops, and on your phone. Anyone can sing, draw or write, and it doesn’t matter what the perceived quality of the work is – that part is subjective. Art is accessible because although there may be some objective standards deriving from the development of particular skills, that doesn’t preclude the untrained person from producing something beautiful.

Art has the potential to be created by anyone, for anyone. For that purpose the arts should strive to be accessible to anyone. It is also the reason we should pay attention to and engage with the production of the arts. Student productions, community workshops and YouTube tutorials make the arts accessible both to people who want to become involved and wider audiences. Exposure increases engagement, and engagement increases attention to the arts. If people engage with and create demand for the arts, the creative industries will expand in what they cover and how they provide it.

Shakespeare is the most enduring and famous playwright, and at least part of the reason for this is because he made his art accessible to a wide audience. What is important is that even if you don’t want to engage with Shakespeare or you don’t like his work, everyone should be able to access it. Shakespeare’s works are absolutely part of the arts, but they are no more so, or less so than a piece of slam poetry you hear at a rally, or a piece of street art on a carpark wall.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.