“The Cold War in the Middle East is heating up”: a refrain parroted by Middle East pundits the world over. In this modern reinterpretation of the Soviet-American original, Saudi Arabia and Iran play the lead roles of bitter geopolitical rivals, dividing the region and drawing supporting actors into two opposing camps.

To those watching local headlines, it seems as though each daily news cycle produces a fresh story pointing to the rising temperatures. With tensions escalating, many debate how close the region is to boiling point. But beyond superficial truisms, what does ‘heating up’ actually mean for the Middle East? And what might ‘boiling over’ mean for the rest of us?

Much like its 20th century namesake, this Cold War is dressed in the rhetoric of competing grand ideologies – in this case, Iran’s Shi’ism and Saudi Arabia’s Sunni Islam – both with a rival claim to global leadership of Muslims. At its core, however, the conflict is a geopolitical struggle for influence between two near-peer powers, each being the only thing standing between the other and regional domination.

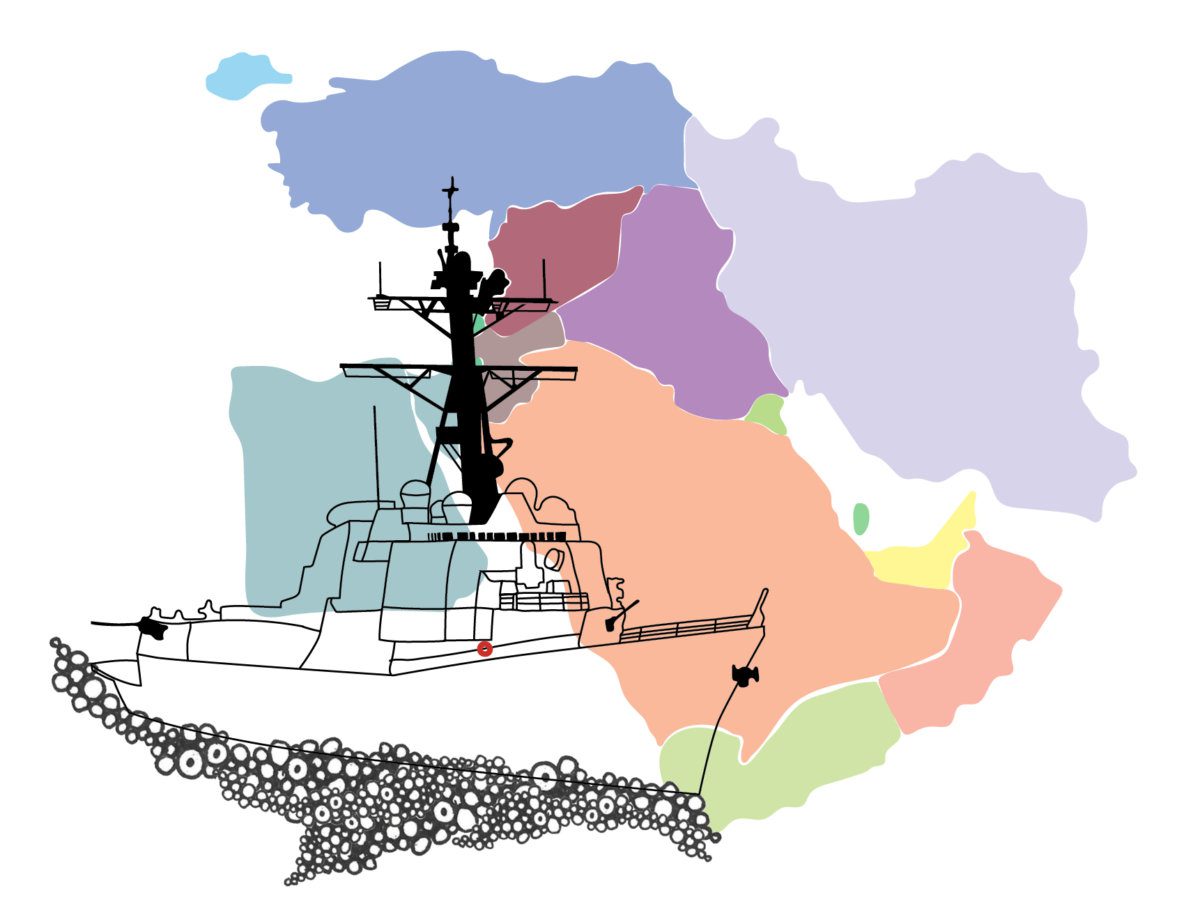

Saudi-Iranian confrontation is playing out across the battlefields of Yemen and Syria, of the Iraqi and Lebanese elections, of Hezbollah, Hamas and Israel. Other incidents that manifest the rising tensions read like a grocery list of Middle Eastern geopolitical stereotypes: assassinations, mysterious disappearances, terror attacks, missile strikes, fire-and-brimstone rhetoric and accusations of political puppeteering.

Despite mounting hostilities, conventional wisdom holds that a direct clash between the two is unimaginable. Indeed, a continental armed conflict seems unlikely. The long and bloody war with Iraq remains fresh in the Iranian national memory, and the costs of the proxy war in Yemen are quickly adding up for the Saudis. Both powers are contending with domestic economic and political challenges. Neither is looking to pick a fight that might threaten the survival of its regime. But, in reaction to a number of factors, states across the region are gearing up for a different war, in a different theatre. If there’s a great-power war coming in the Middle East, it’s going to be fought not on land, but by sea.

The maritime Middle East has always been a critical international arena. But, developments of the 21st century have shifted the global centre of geostrategic gravity towards it more than ever before. The vast energy reserves needed to feed China’s explosive growth and its Belt and Road Initiative have raised the strategic significance of the Middle East’s key straits and the sea lines of communication connecting the Persian Gulf to East Asia. But as these vital trade arteries have grown in importance, they’ve also come under increased threat.

On both sides of the Arab Peninsula, Iran and its proxies wield the spectre of a crippling blockade. In July, the Iranian military threatened to shut the Strait of Hormuz in response to President Trump’s reimposition of sanctions on Iran’s crude oil exports. On a number of occasions, Iran-backed Yemeni Houthis in the Bab al-Mandab have attacked Saudi and US oil tankers as well as US, Saudi and Emirati naval vessels. In early August, these salvos led to a brief Saudi suspension of oil shipments through the strait. Most recently, on 7 October, Yemen’s Saba state news agency reported that Houthi rebels had detained 10 oil and commercial vessels at the port of al-Hudaydah, including an Indian-flagged fuel tanker.

These incidents have highlighted both the vulnerability and the strategic weight of the Middle East’s key waterways. In response, the region is experiencing an unprecedented naval military build-up. States both within and external to the Middle East are desperate to secure the flows of their trading lifeblood, deter attacks, and match their competitors’ growing maritime forces. And it’s this paranoid, hawkish drive that should scare anyone worried about a thawing regional Cold War. The rapid militarisation of an extremely volatile region increases both its flammability and the chance of a spark to set it off.

On both sides of the Saudi-Iranian confrontation, regional powers have scrambled to modernise and expand their naval capabilities. In July, Saudi Arabia finalised deals with Spanish shipbuilder Navantia to purchase five Avante 2200 corvettes and with US firm Lockheed Martin for four slightly larger Multi-Mission Surface Combatants. In so doing, it’s also secured technology transfer agreements to develop its indigenous defence industry for the longer term. Turkey is expecting delivery of its first “light” aircraft carriers in April 2021, in a similar technology transfer agreement with Navantia. Egypt has invested heavily in its navy, launching on 7 September its first home-built corvette. Concern over Iran’s small speedboat swarms has prompted the US to conduct defensive exercises against them using A-10 Thunderbolt II jets.

Heightened maritime tensions have also seen a rush on ports and military bases up and down the Horn of Africa. China chose to establish its first overseas military base in Djibouti; Saudi Arabia and ally UAE have claimed sites there and in Somalia, Libya and Eritrea, while more Iran-aligned Qatar and Turkey have begun construction in Somalia and Sudan. Further stoking regional instability, both Iran and Saudi Arabia have used ports along the Red Sea littoral to smuggle weapons and launch strikes against opposing sides of the Yemeni civil war.

While mutual military build-up never makes conflict inevitable, a maritime clash – by nature, more limited in casualties and scope, and slower to escalate – seems like an increasingly plausible eventuality. It’d be a threat to the Middle Eastern shipping lanes that ballast the global economy, and thus a threat to all of us. Western navies are stretched, smaller than at any point since WWII, and preoccupied with East Asia. Our decision-makers desperately need to divert some of their policy attention and professional panic from overwritten flashpoints like the South China Sea to the difficult multilateral powder-keg that is the maritime Middle East. The also need to remember that Middle Eastern wars do not disappear just because the West is tired of fighting them.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.