—Zelda Fitzgerald, Save Me the Waltz

There are exactly two things that I know for certain:

The first is that wholemeal bagels are a direct result of the rapidly dissolving integrity of the human species, and the second is that Zelda Fitzgerald was brilliant. A perpetually unrecognised genius.

Zelda’s first and only novel Save Me the Waltz (1932) is semi-autobiographical and, like Scott’s later Tender is the Night, predominantly written about the period during the 1920s which the Fitzgeralds and their contemporaries spent in Paris. It is the lesser-known of the pair, but certainly not the less valuable for it. The novel was written by Zelda in a creative fervour of six weeks while institutionalised for schizophrenia (whether or not she actually suffered with schizophrenia is debated—her “breakdowns” are often attributed to bipolar disorder, or alternatively depression or anxiety). When Scott initially discovered its existence, he was furious; his letters, notably to friends including Ernest Hemingway, and industry figures such as editor Max Perkins, disclose his anger at her depiction of him. In a letter with Zelda’s psychiatrist, he wrote:

Originally written, to quote Scott, as a “thin portrait” of their marriage and their characters, in Zelda’s early drafts she went to the lengths of naming the love interest “Amory Blaine” after Scott’s autobiographical protagonist in This Side of Paradise. Afraid that the book would damage his reputation, and angry that she had chosen to write based on the same period of their lives as his then-unfinished Tender is the Night, he convinced her to rewrite it. Eventually, he helped her to edit and publish the novel, and praised its quality. But not before she had made significant changes, which she didn’t appear to resent, and on which we can only trust her judgement as the competent and intelligent writer she has painstakingly proven herself to be.

Save Me the Waltz offers, for the first time, some real insight into the glamorous and turbulent marriage of the Fitzgeralds, as well as Zelda’s thoughts, feelings, and character, beyond what is shown to us in Scott’s work. The female love interests throughout his fiction are, by his own confession, thin portraits of her, his muse. On their marriage, he told a reporter, “I married the heroine of my stories.” At times, he lifted entire passages from her diaries and letters, which Zelda playfully notes in her review of The Beautiful and Damned.

Zelda Fitzgerald has been often viewed as “the original flapper,” “jazz baby,” “wild child.” Rarely “writer,” “artist,” “dancer.” In marrying Scott, she “unknowingly sealed her fate as a symbolic being…as the quintessential muse, artist’s wife, and, eventually, doomed woman—a brilliant but mercurial talent whose public persona subsumed the identity she herself attempted to create and control” (Lawson, 2015).

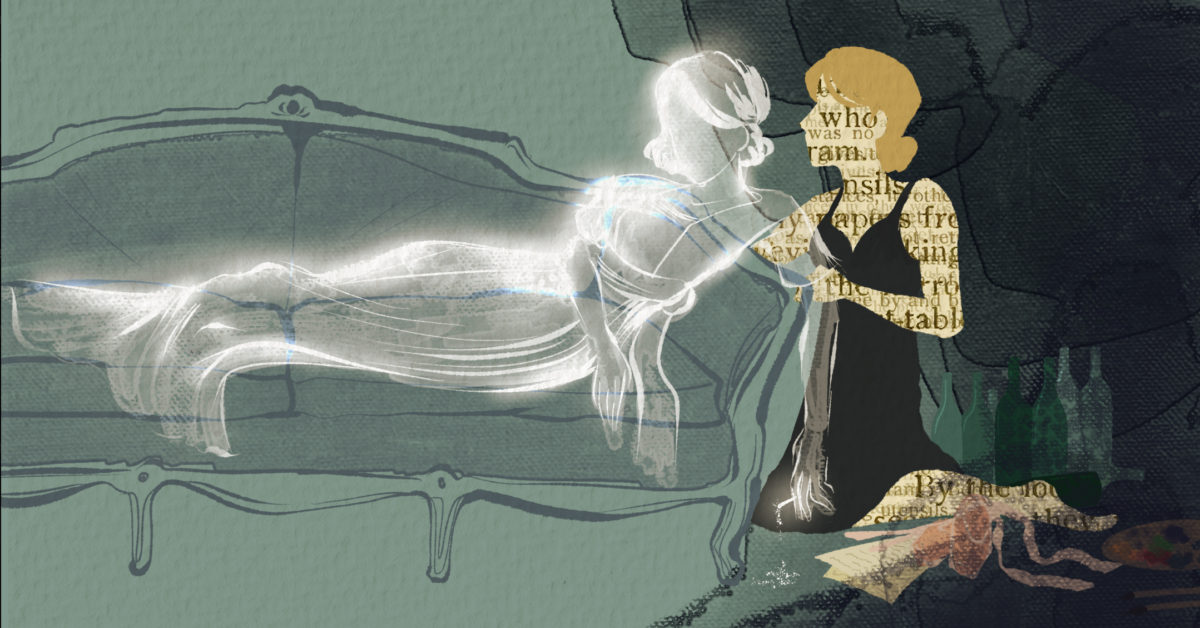

Scott opposed most of Zelda’s creative endeavours; he discouraged her work in ballet, and actively tried to prevent the publishing of her book in its early stages. In Save Me the Waltz, protagonist Alabama Beggs’ husband (David Knight) openly disapproves of her dancing, probably reflective of the author’s own situation. David is a successful painter—thinly replacing Scott’s writing—and refuses to acknowledge Alabama as an artist equal to himself. I don’t believe or mean to suggest that Scott was fundamentally a bad person, or a woman-hater. But he was a romantic, an idealist, and he was validated by the standards of the time in his expectation of a romantic relationship with the dynamic of female muse for the male artist—a tale as old as time, an idea which hasn’t been disrupted or challenged until comparatively recently. He built up an expectation which she fulfilled—friends noted how he would hang on her words, scribble down her comments at parties. She was the heroine of his stories, and things were good, so long as she could be reduced to something two-dimensional, and could be distilled into beautiful words and pressed onto white pages.

But then there was the problem of her incurable brilliance, her capacity as expansive as his for creation. In fact, she excelled in ballet and painting and writing. When she wanted to create, she became something more than the heroine of his stories, rejecting the expectations he had so fancifully set. And this, I think, is where their problems began—assisted, of course, by the excessive drinking, affairs, and inadequate mental health care courtesy of the time.

The overwhelming majority of the—sorely limited—critical attention Save Me the Waltz received on and since its publication has been negative; in the preface of the second edition of Save Me the Waltz, Zelda’s writing ability is called merely “surface level,” (Moore, 1966) repeating the oft-cited criticism of her unusual use of language.

But it is her fantastically imaginative language that makes her writing so wildly unique, so fantastically appealing.

Especially towards the beginning of the novel, she writes to disorientate—metaphors composed of borderline-nonsense; surrealist imagery; wacky, Zelda-devised turns of phrase to make your head spin. And it is truly, utterly captivating.

Caught inside Zelda’s words are feelings of bewilderment, joy, fractured relationships, obsession, hedonism, and beneath it all, a fight for a sense of self. Her style, regularly criticised as unpolished, simultaneously confronts the reader with the glamorous, playful ‘Jazz Age’ and its contorted underbelly of subtle misogyny and the imbalanced perception of one’s own identity.

“He pulled himself intermittently to pieces, showered himself in fragments above her head.”

“She crawled into the friendly cave of his ear. The area inside was grey and ghostly classic as she stared about the deep trenches of the cerebellum. There was not a growth nor a flowery substance to break those smooth convolutions, just the puffy rise of sleek gray matter. ‘I’ve got to see the front lines,” Alabama said to herself. The lumpy mounds rose wet above her head and she set out following the creases. Before long she was lost. Like a mystic maze the folds and ridges rose in desolation; there was nothing to indicate one way from another. She stumbled on and finally reached the medulla oblongata. Vast tortuous indentations led her round and round. Hysterically, she began to run. David, distracted by a tickling sensation at the head of his spine, lifted his lips from hers.”

“Outside the wide doors of the country club they pressed their bodies against the cosmos, the jibberish of jazz, the black heat from the greens in the hollow like people making an imprint for a cast of humanity. They swam in the moonlight that varnished the land like a honey-coating and David swore and cursed the collars of his uniforms and rode all night to the rifle range rather than give up his hours after supper with Alabama. They broke the beat of the universe to measures of their own conceptions and mesmerised themselves with its precious thumping.”

Perhaps even more remarkable than the stylistic depth and character of Zelda’s writing is the means by which she presents the feminine search for self within the early 20th century. Throughout Save Me the Waltz, Zelda uses mirrors as tools for the female pursuit of creative, intellectual, and emotional identity, in a blink-and-you-miss-it subversion of what may be considered the traditional notion of mirrors as tools for female vanity.

Zelda conveys the intrinsic dislocated sense of identity within her protagonist from an early age through mirrors and reflections, introducing the idea towards the beginning of the novel.

“She ran her fingers tentatively through her breast pocket, staring pessimistically at her reflection. ‘The feet look as if they were somebody else’s,’ she said. ‘But maybe it’ll be all right.’”

To David’s displeasure, Alabama takes up ballet during her late twenties, where she dances incessantly in a room filled with floor-to-ceiling mirrors, Zelda thus skillfully entwines Alabama’s near unhealthy compulsion to dance with her unyielding search for identity. It grows into an obsession; a relentless cycle of eating, sleeping, and breathing ballet, despite—or perhaps in part driven by—her husband’s criticism. Alabama’s disjointed sense of self is once again presented in a separation from the psychological and the physical, the mirror and the mind in conflict.

“…she thought her breasts hung like old English dugs. It did not show in the mirror. She was nothing but sinew. To succeed had become an obsession.”

However, before there was ballet, there was David, and Alabama initially sought to find herself in him; she feels that being with him is like “gazing into her own eyes”. But this perception of him becomes “distorted,” having warped her own view of him in a fervent attempt to find meaning within herself.

“So much she loved the man, so close and closer she felt herself that he became distorted in her vision, like pressing her nose upon a mirror and gazing into her own eyes.”

David, however, only looks in a mirror once in the entire novel, in stark contrast with Alabama’s dozens of times, and it culminates in his being “pleased to find himself complete.” Complete. Assured of his identity, recognised as an artist, an individual, certain of his place in the world.

For me, Save Me the Waltz is both joy and melancholy. I wonder if Alabama—which is to say Zelda Fitzgerald herself—ever found what she was looking for. I wonder if, after all the parties and all the laughter, and the breakdowns and the fame and the starlit revelry, she found something that fulfilled her. I hope in her painting, and her dancing, and her writing, she came to some understanding within herself about her world, and her place in it—an understanding that I also hope brought her security and strength of identity.

And so, I’ll leave you with one final urge to pick up the magnum opus of Zelda Fitzgerald (writer, artist, dancer).

Love,

Caelan xxx

Lawson, Ashley. “The Muse and the Maker: Gender, Collaboration, and Appropriation in the Life and Work of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015, pp. 76–109.

Moore, H,T. 1966, Preface in: Fitzgerald, Z. Save Me the Last Dance.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.