Content warning: this article contains explicit mention of self-harm, sexual assault, suicide, passing mention of eating disorders, panic disorder and social anxiety.

It is nearly time to apply for pastoral care positions across campus. The attractions of such a role are clear. For most residential halls, the position comes with a subsidy or scholarship, a larger room, a leadership role. You have access to resources you’ve never had before, and a unique ability to shape the community around you. You can help other people in a tangible way. When you speak, your voice is heard.

However, this role is also fraught. Any person in a residential hall will be familiar with the way their pastoral care team copes as the year goes on. Term 3 brings a lack of faith in the community, Term 4 a state of burn out. Mental illness is abundant, and SRs swap stories of the psychologists they’ve been to, who was good, who didn’t get it. Most spend their last weeks dreading a knock on the door, and wishing for their contract to end.

Each year the positions are advertised afresh. The information sessions talk of portfolio responsibilities and floor events. References to pastoral are limited to a line on a document, or a single, optimistic SR speaking about the good that can be done. There is more to be said. If you are deciding to apply for this role, then you have a right to know what you are signing up for.

The first thing you should know about pastoral care is that you will be bound by a confidentiality agreement. This is a good policy, and it protects students. You will become accustomed to asking for a resident’s permission before you seek advice from staff. You will get used to letting people know that there are some things you must report. Sexual assault and sexual harassment, self-harm and suicide. Any instance where you feel there is danger to the resident or anyone else. Most can be de-identified. The rest you carry with you always, a steel trap of awful secrets.

Sometimes you can help in quick, easy ways. How do I sign up for classes? Where is the Marie Reay Building? Can you help me make a timetable? Where do I get a student card? How do I access financial support, can you drive me to the shops, how do I use the iron? You will give out condoms, and sometimes pregnancy tests, advise on good doctors, and help with extension applications.

The burden of other issues is not so light.

You will refer on to the Canberra Rape Crisis Centre so often that you start to lose faith in your community. You will know the sexual assault guidelines better than you know your course content. You will spend hours with survivors. You will be the first person to tell them that they are believed, and that what happened to them was wrong. You will hold them while they cry. After they have left your room, you will curl into a tiny ball and balance your laptop on your knees as you write up a report.

Every time the name of the alleged perpetrator is revealed to you, you will crumble a little inside. It will feel like a betrayal, and you will avoid that person in the lunch line, unable to tell anyone but the residential staff why you are no longer able to make eye contact. What will you do when a first year tells you that they were assaulted by your best friend’s boyfriend? Or when the survivor and the alleged perpetrator both come to you for support?

You’ll wonder what to do when a resident comes to you about their friend. This friend is suffering from disordered eating, or social anxiety, or panic disorder. You know this friend, but not well enough for them to trust you, and you’ll advise the student to encourage them to come and chat to you together. It will be a fruitless task, this friend does not want help, but they are burdening their fellow peers to the point of harm and it is on you to figure out what to do.

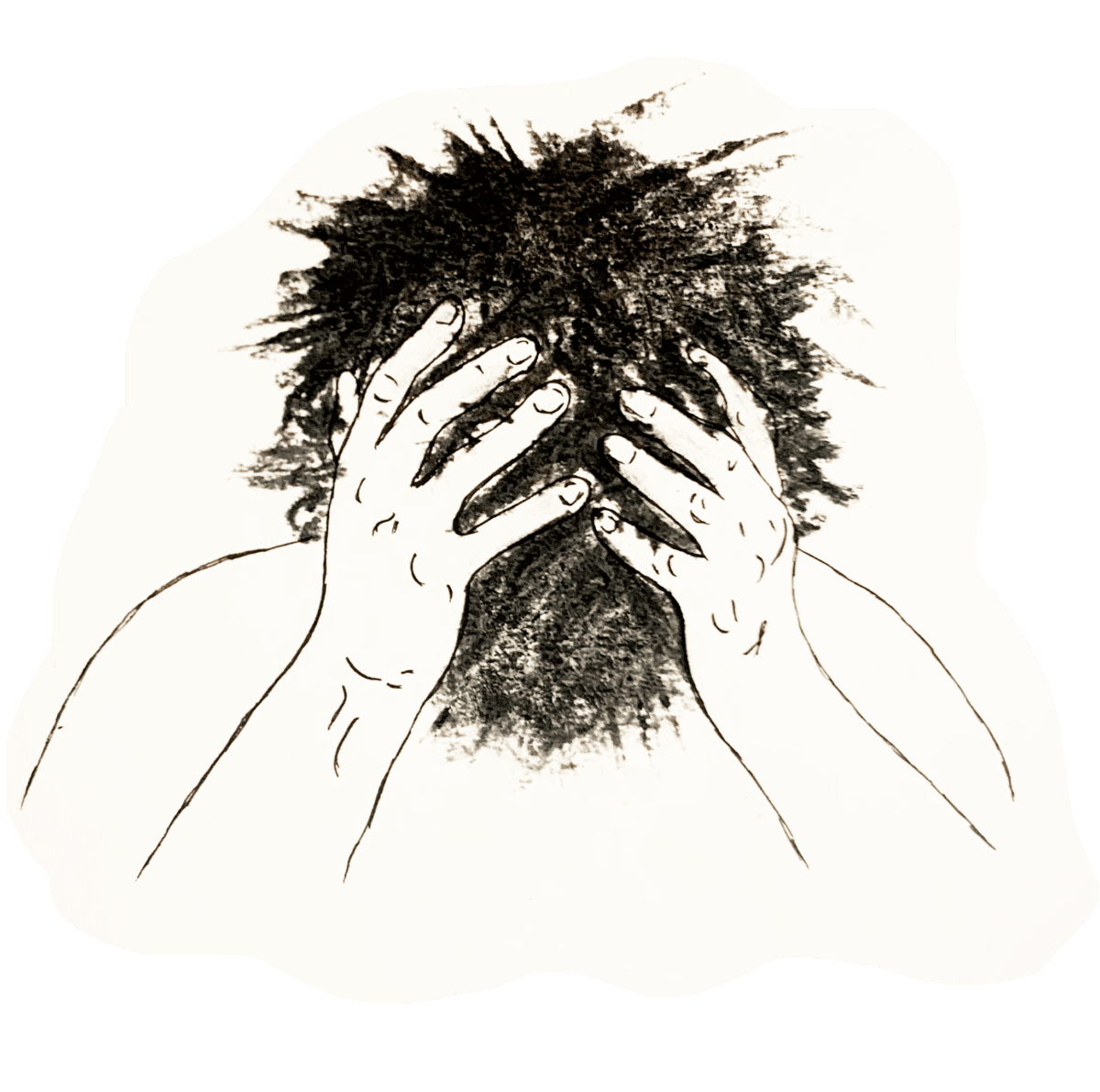

Every time a message appears on your phone asking for a chat, your heart rate will increase. You’ll prepare yourself for the worst. You will traipse back to your room from wherever you are studying, and most of the time you will hear about friendship issues, or relationship problems, or how bad that night’s dinner was. Sometimes though, you’ll bind up self-harm wounds, or make a call to LifeLine, or offer them your bed after they have a panic attack at the thought of going back to where they were assaulted. You will knock on doors, not knowing if the person inside is dead or alive.

The people will come in thick and fast at all times of the day, two chats one day, four the next, and you’ll long for a week off, waiting for the end of your role. You’ll wish you were back in second year, when others were bearing your burden. You’ll drop a course, trying to stop your grades from slipping. Studying will become impossible. You will lie awake at night considering all that you have heard, and all that you might have done.

If COVID-19 restrictions continue, your position is made harder. Employed in what you thought was a caring position, you are expected to play an enforcement role, moving people out of common spaces and asking them not to drink. What will you do when you come across a group of your residents having a beer together on your floor? What if one of those residents was in your room the night before, hugging a pillow and crying as they told you about how lonely they feel, trapped in Canberra at the whim of some state government’s border policy? How will you connect with the residents to whom you owe a duty of care when you are unable to sit down with them in a shared space?

This can still be a valuable role. It is a tangible way to make an immediate difference to your hall. With proper boundary-setting, a lucky cohort of people, and the right support, things can go well. Think about what your residential hall is offering you before you go through your interviews. To attend a hall with multiple on-site staff and small SR to resident ratios should be normal. To have proper training, consistent meetings and free psychologist sessions offered to you is the bare minimum that is required to keep a pastoral care system running. A subsidy or scholarship of some sort is essential. None of these things will stop you from burning out, but they will equip you with the skills and support you need before you wade through the year ahead.

What lies before you is unpredictable, but one thing about this role is certain. If you are applying for a Senior Resident position, do not expect an easy year.

Support services are available here:

ANU 24/7 Wellbeing and Support Line: 1300 050 327 (Monday to Friday 9am-5pm)

Canberra Rape Crisis Centre: (02) 6247 2525

1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732

Lifeline: 13 11 14

ANU Counselling: (02) 6178 0455

Woroni is always open for submissions. Email write@woroni.com.au with a pitch or draft. You can find more info on submitting here.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.