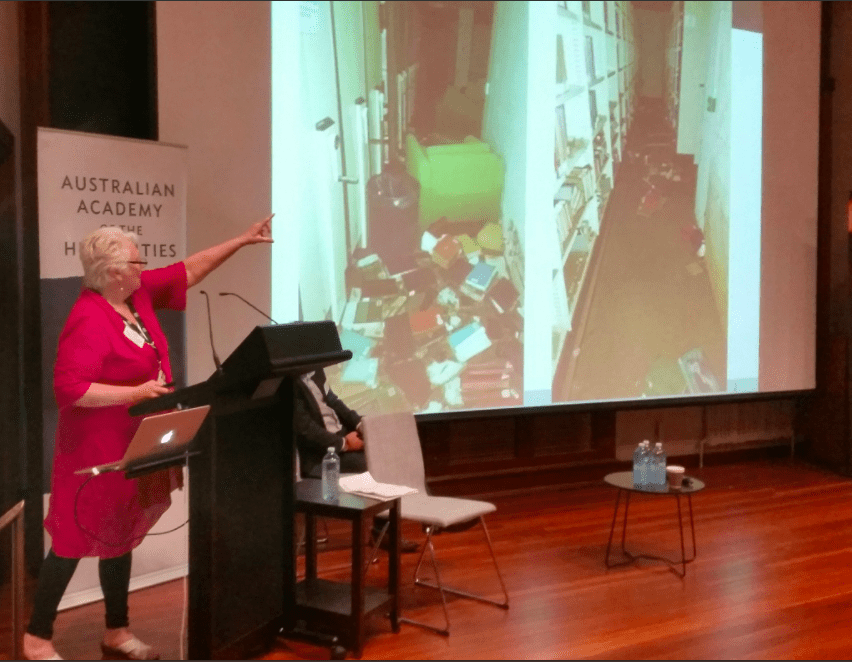

It felt more like a wake than a forum on Tuesday as 50 or 60 academic and administrative staff filed from the Menzies Library foyer into the Macdonald room on the building’s south side. They had assembled to hear from doyenne of Library Services, Roxanne Missingham, and deputy vice-chancellor, Marnie Hughes-Warrington, on the subject of just how badly the Chifley Library and its collection had been damaged by the February flood, and what the emerging strategies were for the epic task of rebuilding that collection over the coming months, years and decades. The forum was a chance for the most affected stakeholders to survey the situation at Chifley with a few weeks’ distance from what was a gut-wrenching and traumatic event.

Until Tuesday, details about the extent of the losses have been somewhat vague. vice-chancellor Brian Schmidt noted in a university-wide email following the flood that “there was significant damage to the library’s microfilm collection relating to literature, politics and current affairs, as well as books and journals relating to history, parliamentary papers, politics, philosophy and anthropology.” In a statement released on 1 March, Missingham reassured staff and students that old and rare books had been spared, and outlined the steps being taken to ensure continued access to the undamaged sections of the library’s collection. She also stated that an expert conservator was assisting the library in its assessment of the damage.

Missingham told those assembled at the forum on Tuesday that the prognosis given by the expert conservator, Kim Morris, was extraordinarily dark. “Prepare for the worst”, he had said. She then described the triad of circumstances which had brought on what was a slowly unfolding calamity. The library’s basement had held the floodwaters for around 24 hours before being drained. That, in combination with high temperatures and high ambient humidity, meant that mould would rapidly thrive and begin sending invisible clouds of spores into the air. Morris told librarians there was a critical five-to-seven day window within which materials could be rescued before catastrophic mould infestation set in. So great was the mould’s drive to multiply and colonise after long lying dormant on shelves and between pages that a book, removed by Missingham within the prescribed window and kept in a staff area at Menzies Library, was found covered entirely with mould within a week.

In the immediate response, librarians determined that priority should be given to those materials which held the least likelihood of easy replacement. Figures in HAZMAT gear descended the stairs to the swamp and painstakingly retrieved the most valuable ephemera: official publications, pamphlets and serials which would likely prove vital to the future work of PhD students and researchers studying subjects including film and indigenous history. These documents were removed to a cold-storage facility where they can now be kept at -18℃ for up to twelve months. Further action will need to be taken, however, as freezing functions to deactivate mould spores rather than kill them.

The microform collection, which inhabited the many rows of waist-high cabinets on library’s first level, was hit particularly hard. “Mould loves gelatin,” explained Missingham. So immediate and total was the damage to the microfilm and microfiche that VC Schmidt had afforded it top billing in his initial communiqué; print losses were acknowledged second, perhaps reflecting the early optimism that with swift action and expert consulting, monographs which had been spared direct contact with the flood waters might be recovered. That optimism, held by many in the student body, has not been borne out.

The sheer force of the inundation had made a clear impact on both speakers. “When it came,” said Roxanne Missingham, “it came with a force of nature.” As she had already done in a blog post Tuesday morning, Marnie Hughes-Warrington emphasised the word “punched” in describing the violence with which the heavy tables, buoyed by dark rushing waters, had crashed through walls and into shelves. The water that entered the building, Hughes-Warrington explained, was classified “black water, which is contaminated water.” It entered from outside after breaching Sullivan’s Creek, but it also came from within when the library’s plumbing backed up, pushing sewage up through the drains and toilets. Water containing high levels of dissolved carbon compounds and pathogens from waste matter then wicked gradually upward through millions of tightly compressed pages, causing books to swell and form strange snaking rows along shelves where horizontal expansion was no longer an option. Compacti strained and then buckled under the tonnes of additional water weight, rendering whole swathes of the collection inaccessible for days in the stinking warmth.

The result, the Chief of Library Services and deputy-vice chancellor jointly confirmed, was that virtually the entire floor, covering sections ‘A’ to ‘Du’ of the university’s collection, had been lost. It is estimated that this constituted up to ten percent of the ANU’s collection. To use the word decimation therefore is no overstatement. In addition to the materials now on ice, 2024 items which were out on loan at the time of the flood were spared. Hughes-Warrington described the decision to remove the entire collection from the building — a necessary precaution lest mould spores make their way upward to the remaining collection on levels three and four — as gut-wrenching.

Attendees of the forum heard that a list of the damaged materials had been sent to the National Library of Australia, and that it was understood that of the more than 100,000 items lost to the flood a mere 30, some of which were in Russian, were not known to have copies held in any other Australian library. It is an incredibly positive result and yet somehow felt like a near miss of the bullseye. Since Tuesday, however, the losses have been cross-referenced against a more recent and comprehensive database, and that figure has been happily revised down to two. Two out of 100,000.

Once the state of affairs had been made clear, the floor was turned over to the audience, and the first questions were decidedly pragmatic. Dr. Catherine Frieman, senior lecturer in Archaeology, sought a list of the lost works so that she and her colleagues might begin the difficult process of selecting and seeking out those teaching materials deemed high priority. Frieman also suggested that a shuttle be arranged to transport students and researchers between the ANU campus and the National Library. While the prospect of distributing a list of over 100,000 works was deemed to be unfeasible, the suggestion of a shuttle service was received gratefully, and Missingham subsequently told me that Joanna Fitzpatrick, associate director of operations at Facilities and Services, put the case for five daily trips between the ANU and NLA to chief operating officer Chris Grange this week. It was also determined that lists of all honours and PhD students whose research was affected by the flood would be handed to Missingham by their respective schools, and the chief librarian pledged that library staff would work closely with those students to ensure that necessary materials were promptly provided. Tom Worthington of the Research School of Computer Science asked the blaring question of whether flood mitigation strategies were being reviewed, to which Marnie Hughes-Warrington responded in the resounding affirmative.

Dr. Paul Burton, Senior Lecturer in Classics, wondered whether librarians’ lives could be made easier via the flagging of items known to be unavailable in the catalogue of Bonus+, the resource-sharing program which allows post-graduates and staff to borrow from other university libraries. It is worth noting that Bonus+ will be made available to undergraduates as part of the effort to ensure continued access to materials. Both Missingham and Hughes-Warrington beamed at the suggestion, apparently as much for its symbolic meaning as for its practicality. Expressions of concern for the trauma which this event has inflicted on librarians go quite a long way. These workers are specially trained to be the gatekeepers of knowledge, to point out doors which open onto information that a student or researcher might never have thought to seek. They tend their libraries like gardens, maintaining order, organising their contents to make patterns intelligible to the human senses. In February they were informed that their domain had been wantonly vandalised by the waters of the neighboring creek, and asked to stay home. For the last several weeks librarians have been moved to new buildings, integrated into existing workplaces, made the best of ad hoc conditions, and experienced uncertainty about what might greet them upon returning to Chifley. For Roxanne Missingham’s part, work days ending well after 1am have become the new norm. Mindfulness and solidarity are, of course, perennially valuable. At the present, however, their communication in interactions with our librarians, particularly those from Chifley, is priceless. As Hughes-Warrington put it, the “Tim Tams and sympathy” are what make the biggest difference.

By this point the mood in the room had passed from its initial quiet dread, through the shell-shock of learning that so much had been lost, and elevated to the brisk, no-nonsense tone that often accompanies cooperation in the face of adversity. As the topic of discussion turned to what one questioner termed “the philosophy of replacement”, however, the atmosphere became noticeably more tense. Hughes-Warrington had earlier identified some scope to “reimagine” Chifley, and I watched the word being jotted down by attendees on either side of me. Now, the questioner opined that “paper’s nice, but for a working university library electronic is really going to be more appropriate.” Roxanne Missingham recognises the value of digitised resources: in her former role as parliamentary librarian, she oversaw the digitisation of federal hansard back to 1901. After she spoke about this and the usefulness of searchable documents in research, some at the meeting inferred that the ANU’s hansard collection and parliamentary papers would be replaced in a purely digital format. This is not the case. The subtext of this discussion was the debate about whether some experiential element of reading is lost when a book is consumed in a digital rather than paper format. It is a touchy topic for some, and largely subjective due to its aesthetic dimension. The “physicality of reading” was invoked by one member of the audience, who warned of the loss of the relationship between reader and author. It is clear that there exists a feeling of apprehension among some, though not all, in the affected faculties that the rehabilitative process may result in some restructure or rationalisation of the library’s collection.

But Missingham and Hughes-Warrington were naturally prepared for these kinds of questions, and acutely aware of the need for both physically and digitally accessible resources. For Missingham, it is Chifley’s very status as a working university library which makes the presence of rows upon rows of books so vital to its function. She views the act of browsing as a mode of interaction with the library not to be underestimated, and with a wry smile noted to the audience of academics on Tuesday that “it is possible to convince the librarians at the National Library to let you into the stacks,” which are typically off limits to the public.

Marnie Hughes-Warrington puts it more bluntly: “books are critical,” she tells Woroni. For her, a philosopher of history who has written on the subject of marginalia, the thought of the permanent erasure of the “interesting and sometimes completely insane” scribblings made by students in the pages of old books provoked a barely perceptible crack of the voice. For some these often furious dialogues between anonymous readers and handsomely embossed authors represent the first motions in the churn of academic debate: today’s scribblers are tomorrow’s interlocutors. Physical books are necessary for these interactions to occur; ebook databases like Routledge and Oxford Scholarship Online are unlikely to introduce public comment sections to their platforms any time soon.

The attitude of both Roxanne Missingham and Marnie Hughes-Warrington is that the process of rebuilding the library’s devastated collection must involve a steady stream of communication with heads of schools, educators and researchers. In this way the most urgently needed materials can begin to repopulate Chifley’s shelves as quickly as possible. Of course, the very necessity of prioritisation itself raises further complexities. A question was raised by historian Alex Cook about how the library might avoid a scenario where books which aren’t specifically required by staff or students are simply never replaced, pushed inevitably to the back of an ever-lengthening queue of materials deemed of a higher priority. “You can’t. You just can’t,” came a disembodied voice from behind me. But this pessimism flows from a place of uncertainty — it may be mitigated with ample consultation.

It will likely be years before the Chifley Library collection begins to resemble its former self. Hughes-Warrington told Tuesday’s forum that “sometimes it will feel like we’re making progress, at other times it’ll just feel completely abject.” Today, however, in the first sign of progress tangible to students, the library will reopen its doors for the first time. Hughes-Warrington had said that the resumption of the building’s air-circulation facilities would be a “big breakthrough”, a threshold moment. There will likely be more of these behind the scenes, as the library has already begun fielding enthusiastic enquiries from the ANU community and its periphery about donating money and materials. This spirit of generosity has raised another quandary for Missingham, who says “the question is: where do we put things?”

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.