The Turnbull government’s recent axing of the 457 visa category has left international students and academics facing uncertainty about their ability to attain citizenship in Australia in the future.

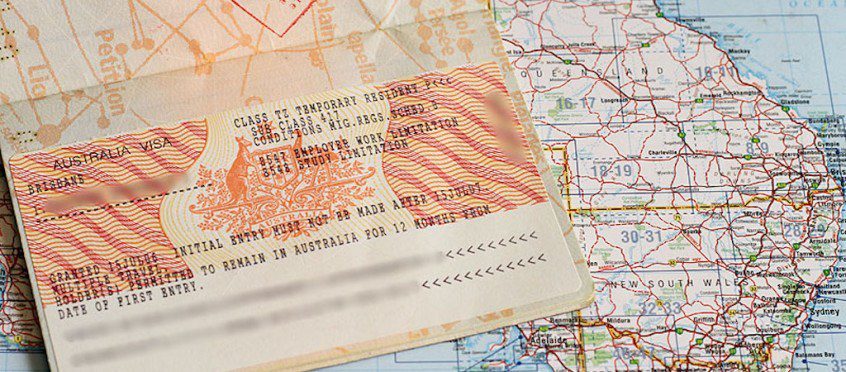

The 457 visa program allowed businesses to employ foreign workers for a period of up to four years, in skilled jobs, when there was deemed a shortage of Australian workers. The visas came with a lot of special provisions: the numbers were uncapped, the recipients could travel to and from Australia without limit, and they could bring their families with them.

As of September 30, 2016, there were 95,757 workers in Australia holding a primary 457 visa, and 76,430 individuals holding a secondary visa, who are members of the primary holder’s family.

But with the government’s changes, announced in a Facebook post last week, this system will be split up into a two- and four-year visa. The two-year visa would only be available to a shortlist of jobs, and would not permit residency at its conclusion, while the four-year visa program would enable highly skilled migrants to seek permanent residency, pending an English language test and a background criminal check.

The announcement has been hit with backlash, particularly in the tertiary education sector.

The ANU vice-chancellor, Brian Schmidt, was one of the first to hit back. Having arrived in Australia from Harvard after finishing his PhD in 1994, Schmidt would only have received a two-year visa under the new system, which would not have given him enough time to conduct his award winning work in astrophysics.

Schmidt told The Australian that the ANU’s capacity to employ academics ‘would be of paramount concern’.

‘My hope is that the status quo – where academics can move freely in and out of Australia – should be maintained. We would be very concerned if we were restricted in hiring academics from abroad based on any criteria,’ he said.

ANU has around 240 staff currently on 457 visas. Under the changes, no one who is currently under the program will have their visa changed – the policy only applies to skilled foreign workers who apply in the future.

But this is still enough to fuel uncertainty in the tertiary education sector. Professor Peter Hoj, the chair of the Group of Eight, a group of Australia’s leading universities, said: ‘At face value the new technical arrangements for the temporary skills shortage visas and employer sponsored permanent skilled visas may make maintaining Australia’s international advantage more difficult.’

‘More broadly, the mere suggestion of the government clamping down on academic mobility into Australia could deter potential academic recruits to Australia. This is particularly a concern at a time when there are opportunities for recruitment from the US and the UK and initiatives under ways such as the recently announced Go8-India taskforce tasked with developing PhD and researched mobility between Australia and India,’ he said.

Henry Sherrel, a researcher at ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy, further argued that this would disadvantage Australia when it came to its international academic competitiveness.

‘Removing the ability for many migrants to become permanent residents after spending a period of time in Australia will make it harder for employers and other organisations like universities to attract global talent.

‘Both “chief executive” and “university lecturer/research fellow” will be restricted to the Short-Term Skilled Occupation List. This means they are eligible for a two-year visa, able to be renewed once, but ineligible for the common permanent employer-sponsored visa, the Employer Nomination Scheme.

‘Imagine being the chairperson of a Big Four bank or major law firm and not being able to offer potential chief executive officers a five-year contract due to visa restrictions? Innovation is difficult when universities are unable to hire the best people in the field, as higher education research is truly a global labour market,’ Mr Sherrel said.

Across the 39 major Australian tertiary institutions, over 2000 employees will be affected by this policy change. Among their numbers is Dr Erin Vaughn, who moved to Canberra from the US last year to undertake research at ANU. Both her and her husband are on primary 457 visas for scientific research jobs.

Speaking to the ABC last week, Dr Vaughn said: ‘A crackdown on 457 visas terrifies me, frankly … I’m not sure how it’s going to affect my family and I’m not sure how it’s going to affect my future job prospects.’

‘I think that it can do nothing but harm universities and the researchers here in Australia.’

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.