Every year, the ANU releases its annual report, a breakdown of the institution’s finances, work and decisions in the past year. The ANU tables the report to Parliament, and includes a self-evaluation of the ANU’s Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) – their strategic goals.

The report is fairly dry, so we’ve broken it down and summarised it for you. The full report can be read here. Below is a snapshot.

As previously reported, the ANU made $150 million last year, amid mass staff layoffs and course cuts. The Report dives into other aspects of ANU finances, such as Vice-Chancellor Brian Schmidt’s salary, what firms the ANU invests in, and how much money the ANU makes from parking.

Despite the ANU insisting on a return to campus this year, and residential halls arguing that students cannot cancel contracts because COVID-19 is no longer an unforeseeable event, the ANU did not evaluate seven out of 12 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), citing the pandemic. See more in the KPI section, which also looks at how effective the ANU’s measurements are.

If you read one thing in this report, it should be this: the ANU wants demand for places here to outstrip the number of positions they offer, “…consummate with the comparative situation at the world’s highest ranked universities such as Harvad, MIT, Oxford and Cambridge.”

Another common way of ranking universities is by employability – the number of students who are employed in the field they want once they graduate. QS determines employability based on

“…institution’s employer reputation, graduate employment rate, alumni outcomes and more.” It ranks the ANU as equal fifth in Australia for employability, and 66th in the world, behind other domestic universities, and behind Harvard, MIT, Oxford and Cambridge.

Finances

The ANU’s net assets have grown to $2.9 billion, and its total income last year (most of which is non-operational and cannot be spent) was $1.5 billion.

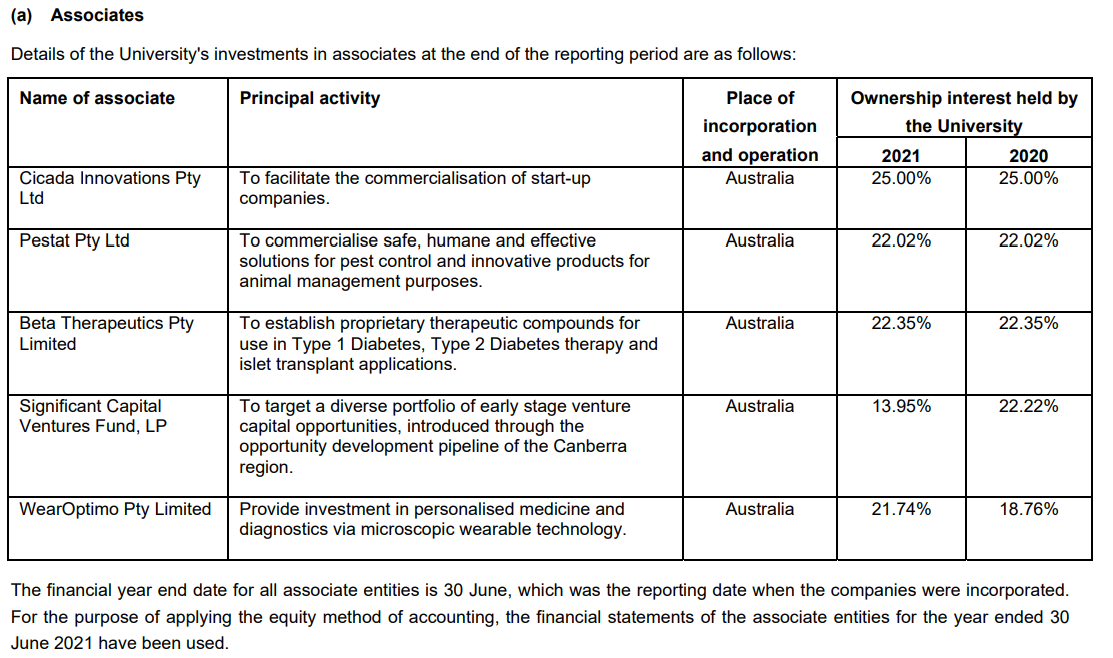

The Annual Report provides interesting details not only on university spending, but also corporate investment. The ANU owns significant stake in several startup and venture capital firms, listed below:

These investments have the highest level of investment from the ANU, with their principal activities listed in the table. For many of these companies, the ANU is actually a pivotal investor. WearOptimo Pty Limited, for example, lists ANU as its “cornerstone investor” on its website, while having the lowest level of investment in the table.

Cicada Innovations is the ANU’s largest investment, and facilitates the commercialisation and development of start-up companies and venture capital firms. On its website, it claims that, from 326 “resident” companies, it raised $1.3 billion.

An example of the companies Cicada Innovations invests in is Cancer Aid. Cancer Aid is a palliative care program that seeks to help cancer patients through the process of the illness. It’s unclear what its financial model is, but it does pitch its services to business with the following graphic:

This could suggest that Cancer Aid is seeking to improve the productivity and output of cancer patients.

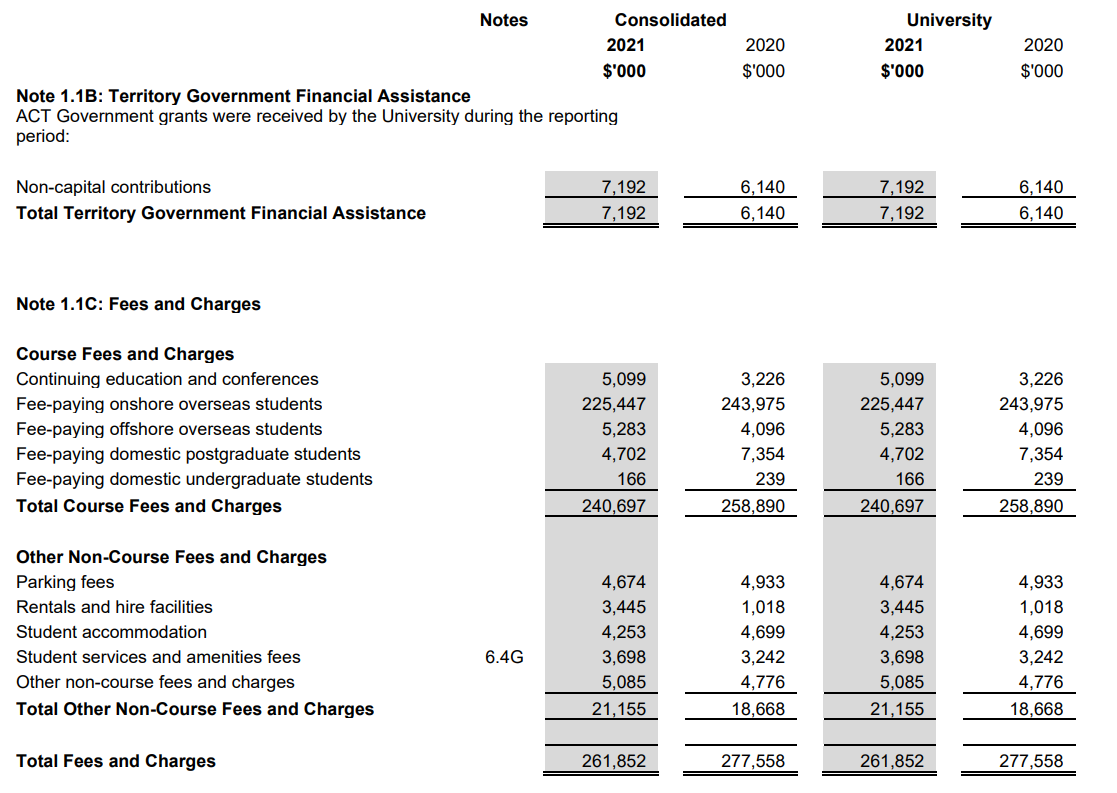

The report also reveals that domestic undergraduate students are one of the smallest revenue sources for the ANU. The breakdown can be seen in the table below. Amongst other things, it shows that the ANU’s biggest revenue source is onshore overseas students, followed by educational conferences, postgraduates, then domestic undergraduates. When we include government support, the revenue from international students is about double that from domestic undergraduate students. However, the ‘overseas student’ figures do not distinguish between undergraduate and postgraduate students.

If you thought parking on campus was expensive, and that paying rent leaves you hard-pressed by the end of the week, know that ANU makes $4.6 million and $4.2 million from these sources respectively. The revenue from parking excludes any fines.

As part of its response to COVID-19, the ANU reduced rent for many businesses on campus. The Report states that “Rent reductions varied from 20 percent to 100 percent depending on the level of government restrictions in place in the ACT at the time.” Students living on campus did not see any rent decrease in 2021, and students stuck in other states during lockdowns had to continue paying rent even when not living at the residential hall.

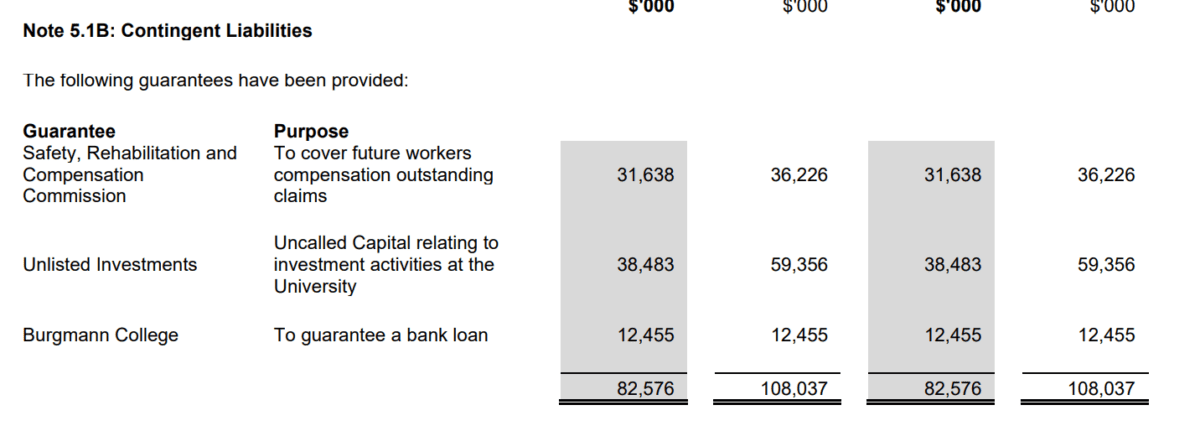

The Report lists the ANU’s contingent liabilities, including guaranteeing a $12 million loan to Burgmann College. The ANU confirmed this has been guaranteed since 2003, but did not comment on what for.

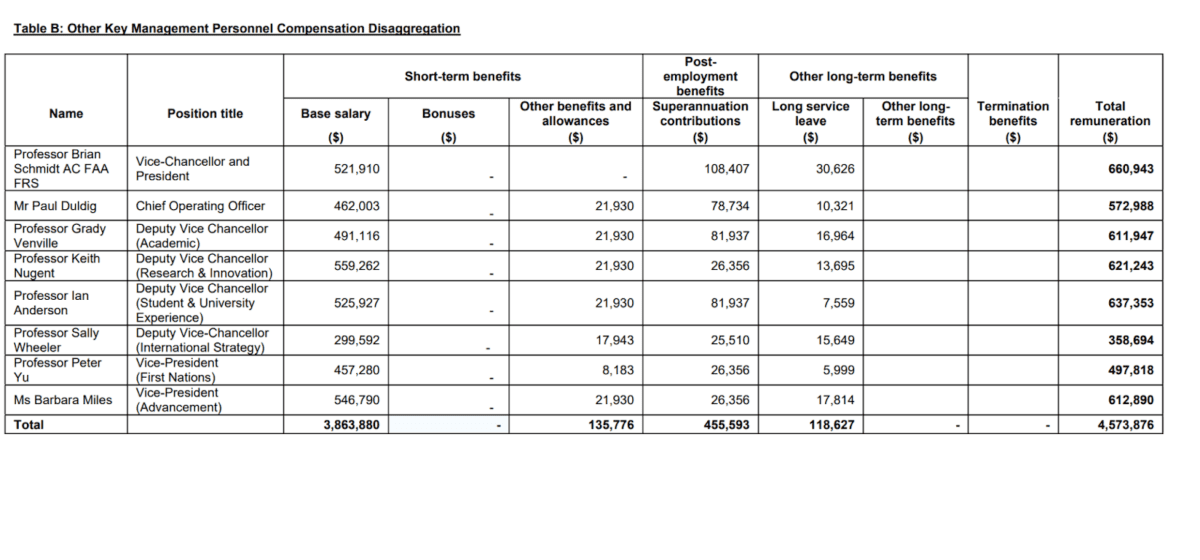

Further, the report gives a statement of salary and total remuneration of ten ANU Council members, along with attendance at the various council meetings.

If you’re wondering how he affords his Tesla, Prof. Brian Schmidt unsurprisingly led the executive remuneration last year with an eye-watering $660,943. Schmidt had a middle-ranged salary of $522,000, however his superannuation contributions and long service leave make up the difference. While Schmidt gets no benefits or allowances, he does get a superannuation contribution around $20,000 higher than the next two professors, Grady Venville and Ian Andresson. These two do get a benefits allowance of just under $22,000.

Professor Grady Venville, who you may recognize as the person to announce PARSA’s defunding, did well with $611,947; while the Vice-Chancellor (First Nations) Peter Yu and Deputy Vice-Chancellor (International Strategy) Sally Wheeler kept the rear with a $497,818 and $358,694 respectively.

All up, the remunerations for the eight most highly paid executives added up to just over $4.5 million, which is a million more than what was spent on student amenities and twice what the undergraduate union, ANUSA, received.

The University Council was well attended with only ministerial appointees Michael Baird and Tanya Hosch missing meetings. Elected Student Member Christian Flynn attended the only meeting he could, and Chancellor Julie Bishop attended all six. The rest of the council meetings were similarly well attended with the notable absence of Brian Schmidt at meetings of the Finance and Campus Planning committees.

KPIs and Overall Performance

The ANU’s yearly performance is measured through the administration of 12 Key Performance Indicators (KPI), seen below. In 2021, the ANU failed to meet three of the seven assessed criteria. The University did not assess the remaining five KPIs, citing COVID-19 interference. For example, the ANU did not formally assess contribution to public policy, claiming COVID prevented “formal external review.” Instead, it provided four anecdotes detailing meetings with government officials.

ANU’s responsibility to Indigenous Australia

The ANU noted that statistics pertaining to Indigenous student completions may be smaller than other Group of Eight (Go8) universities, due to the ANU’s “small size.” However, by using 2020 Department of Education data to identify completion rates at Australian universities, both of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, we find that ANU had 32 Indigenous students complete their degrees, out of 7236 undergraduates; 0.44 percent of degree completions were First Nations students. The national average proportion is 0.81 percent, meaning that the ANU’s ratio is around half the national average.

The ANU provided information about Indigenous student enrolment but did not formally assess this KPI, as University leadership believe the KPI should be reviewed.

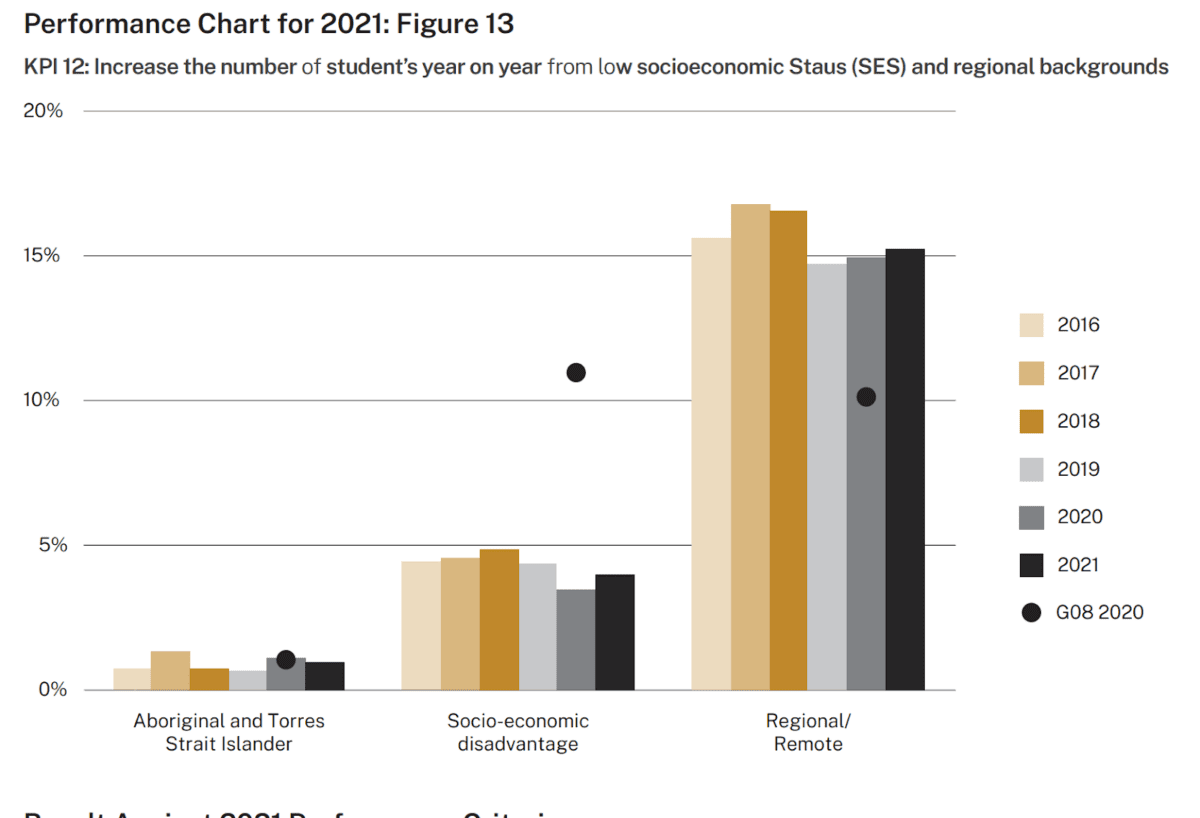

Increase the number of students from low-SES and regional background

The ANU student body is composed of less than 5 percent low-SES students; well below the Go8 average of over 10 percent. Furthermore, the ANU utilises the Department of Education definition of “low-SES”, which is determined by an SES score the Australia Bureau of Statistics assigns to the address nominated by domestic students (using the SEIFA Index).

Students without a permanent address in Australia, namely international students, are excluded from SES statistics. Notably, ANU students living in residential accommodation may list their ANU address, not their home address, impacting the accuracy of results.

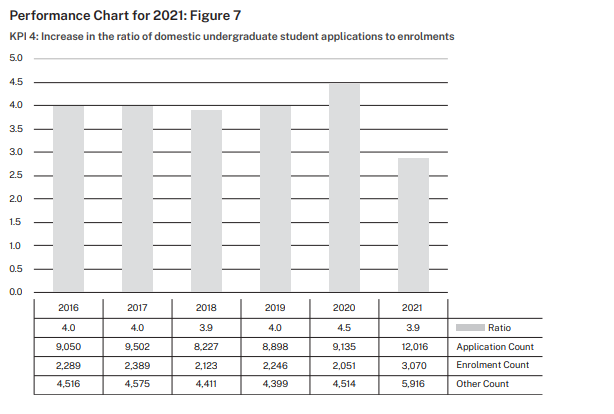

Increase in the ratio of student applications to acceptances

A yearly goal of the university is to increase the ratio of rejections of applicants; citing a desire to compare to highly ranked universities such as Harvard and Oxford. The ANU failed to realise this goal in 2021, dropping to a ratio of 3.9 compared to 2020’s 4.5 applications for every acceptance.

Important to note is that the ANU still offers places to about 50 percent of students – in 2021, the ANU offered 5,916 places out of 12,016 applications, but only 3,070 students ended up accepting their offer and enrolling.

Achievement of recognition of Gender Equity through the SWAN program

The ANU identified improvements in the promotion rates of female academics, with at least 80 percent of female applicants receiving promotions, when compared to a baseline of 67 percent in 2020. However, these statistics do not differentiate staff statistics based on academic faculty. We can take a deeper dive into gendered hiring at the ANU using Department of Education 2020 staff data, shown below:

These statistics show a great discrepancy in the employment of non-male identifying academic staff. Only in Health are there more non-male staff than male, followed by creative arts which just reaches parity. This KPI was marked “Achieved”.

Student Satisfaction

Student satisfaction increased from 2020, which the ANU acknowledged was largely a recovery from COVID-19, both lockdown and online learning. Student satisfaction has not returned to pre-2020 levels.

The ANU’s 2021 Annual Report presents an image of the university that some students might not relate to. For example, the only mention the report makes of sexual assault is a professor’s criticism of sexual assault and harassment in federal parliament. There is no mention of the student divestment referendum passed last year. Additionally, it is unclear how many students relate to, or support, the ANU’s desire to be the new Harvard. And while some students see their programs disestablished, courses cut, or teachers dismissed, key ANU management staff are paid enough to put them in the top 1 percent of Australians.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.