Woroni sat with Liz Deep-Jones to discuss her work, life and experiences with racism. Deep-Jones previously worked at the SBS where she produced the first ever Mandarin news show. She has published a book about football, Australia and class differences, and curated the exhibition We All Bleed the Same which now sits in the foyer of the Research School of Social Sciences. Deep-Jones ran an ANU MasterClass with ANU students who helped to produce the exhibition.

To start, can you tell us about your work as executive producer for the SBS Mandarin News and Current Affairs show? It hosted many prominent figures, such as Julia Gillard, Kevin Rudd and the Dalai Lama. What inspired you to produce Mandarin news and what were your experiences with these high-profile figures?

First of all, I think it’s important to give a little background of the start of my career at SBS television because it led me to this point of becoming the executive producer at the Mandarin news and current affairs show. That show was one of the best and most incredible experiences of my life, I really loved working on that program.

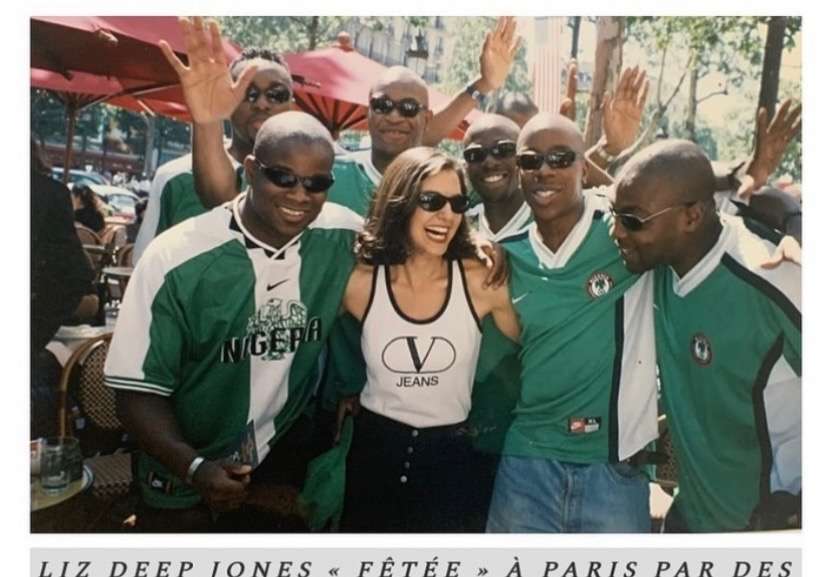

I started at SBS in sports news, and I always loved sports, but my real passion was news and current affairs, and I wanted to work my way into that. I was very fortunate, I’d actually previously been working on a youth suicide documentary through through a separate production company for SBS television. And that gave me a foot in the door.

I actually really loved sports coverage and got to interview some incredible people, such as Nelson Mandela, through the sports program, because my focus was always more the political side and news and current affairs side.

I continued working at SBS and NITV (National Indigenous Television) for a long while. Then I left to write some books and then I was approached to produce the Mandarin news and current affairs show. It was an idea that came from SBS television, but they needed someone that had the experience of producing news and current affairs and reporting and also I knew all the departments in SBS. I was able to bring in the right people for the particular roles that are needed. They’d never done a Mandarin news and current affairs show on television at SBS before and it was an in-language program which I produced, and spoken in Mandarin with English subtitles.

We had to build the program from scratch where even the autocue needed to be in Mandarin for the Mandarin presenter and they had never done that before at SBS so we broke a lot of, I suppose, new ground. I chose a presenter who was a radio journalist. I wanted someone that was a journalist, not just someone that was reading the autocue, because I believe that the person presenting your program needs to know what they’re talking about and have that experience of storytelling and being out on the road reporting. And then we chose the reporters who were also, obviously, bilingual.

We wanted to really make a big splash with our first program. I knew that the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd was proficient in Mandarin. Obviously, he was someone that was on the top of our list, and we were fortunate at the time, actually, because he was foreign minister (after Gillard’s takeover). And we were just lucky that he said yes and his department said yes. He was our first main interview on the program and that was an incredible experience, because we had to fly to Canberra to do the interview. Then, after having set up in the courtyard, there was a North Korean missile crisis, and we thought we were going to lose him because that takes precedence. I was determined to get him. We waited for hours and finally I went banging on the door to see his chief of staff and I begged her, and told her we could do it in just 20 minutes. But we ran over time, interviewing him for our show and then asking questions in English about the missile crisis. At one point the chief of staff stopped the interview and our presenter stood up and said “Excuse me, I’m not finished yet.” And the weird thing was my daughter at the time was a very big Kevin Rudd fan, and I had to hand him this letter after running over time as well. He accepted the letter, and he was whisked away, but Rudd was very touched by the letter and ended up sending her a Christmas card.

I wanted to ask as well about your books, because you left the SBS to write some novels, but now they’re being re-published right?

I’m very excited at the moment because I’m launching Lucy Zeezou’s Goal and Lucy’s Zeezou’s Glamour Game, my series. They were originally printed in 2008 and 2010 and they’re being republished again. It’s about a young girl chasing her dream to be a footballer against her parents’ wishes. She’s Australian, Lebanese and Italian. Her father was a very famous footballer in Milan, Italy and comes from a very wealthy family. Her mother was Australian Lebanese, so she spends her time between Milan and Sydney. But for her, football is in her blood, it’s the only thing she wants to do. She’s got everything materialistically – they’re wealthy, they have a private plane, houses all over Europe and in Sydney – but that doesn’t mean anything to her when she just wants to play football. She befriends a young boy whose Indigenous and its a shared story about their parallel lives, especially because he’s homeless. His parents died in a car accident.

We’re launching it for the upcoming Women’s World Cup in July this year. I wanted to reignite the series and give young footballers the opportunity to read this story about chasing your dream and being true to yourself. Life is short and you want to make the most of it, squeeze every little bit out of it. You lead a full life when you do something you’re passionate about, and it’s rewarding when you feel that you’re making a difference.

You do see that in the We Bleed the Same exhibition, which definitely did make an impact for ANU students. It’s on display at the Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS) building. What inspired you to create that exhibition and why did you decide ANU was the place to display that?

I have been combating racism all my life because I’ve been subjected to racism. I’ve been told to go back to where I came from. I’ve been told “you’re pretty for a Lebanese girl.” I’ve been told, “Oh, you’re Lebanese, can’t help bad luck.” My parents were subjected to racism in our fruit and vegetable store. They had “wog shop” painted in red on the front of their shop. They were called wogs, they were called dirty and smelly. You know, all sorts of derogatory things. But my father always stood up for himself, he was a small businessman, and the business was successful so I think he felt empowered because they were on his property. He would kick people out and sometimes chase them down the street!

But we grew up with it. I felt the impact. I mean, I was afraid of people. The representation of someone that was Australian was someone with blond hair and blue eyes. I grew up wanting to have blonde hair and blue eyes. I have dark skin, dark hair, and dark eyes. I used to spend my time putting lemons in my hair to try and make my hair blonde, because I thought that’s what an Australian looked like. I never saw myself represented in any of the media, in magazines, on television or anywhere. When I saw a group of Aussies across the road, and I was walking down the street, I would cross the road and not walk near them, because I would be afraid that they were going to tease me or call me names. It was very hurtful and it takes away your self esteem and it makes you feel like the other, it makes you feel like you don’t belong. It took a long time for me to really feel comfortable in my skin.Don’t get me wrong, I loved having olive skin, and that I could tan very easily. I didn’t have to wear sunblock then. But I never felt like I fit in.

My dad bought us up to be Australian. We used to go to the beach every morning, I love my meat pies, I love Vegemite on toast, I love my barbeques. But I’m also extremely proud of my Lebanese heritage, and feel so privileged that I grew up in a Lebanese household where we spoke Arabic. But back then, I was afraid and ashamed to speak my parents’ language. I told them not to speak in Arabic in front of my friends, and I used to ignore them and pretend I didn’t understand them. It breaks my heart that I did that to them.

With We All Bleed the Same I wanted something that was long format, and long standing. It wasn’t just a news story or something you watched for a while then it was gone. I felt that through photography, people sharing their stories, and with the portraits. In an exhibition, it’s not as confronting for people, for the general public, to come in and have a look at the beautiful photographs, and then from there, they read these extraordinary stories and what a lot of these people have experienced and endured. And the exhibition is also about the champions of human rights, fighting for human rights, fighting for equity in our society. It took me a long time to get this exhibition together and it wasn’t until I left SBS television a couple of years ago, that I finally had the time to really focus on it and put this together. It was through Addy Road Community Organisation in Marrickville, Sydney, that I and an SBS colleague, volunteered for a campaign called Racism, Not Welcome. There’s a whole group of us that put these signs up all around Sydney and in fact, across Australia. It was through Western Sydney Council, and I applied to them for funding for We All Bleed the Same. They gave me $5,000 and the exhibition first showed at Addy Road Community Centre.

I was lucky. Tim Bauer, the photographer kindly donated his time and we photographed close to 35 people from different backgrounds, races and religions. He photographed them and they shared their stories and I also produced the documentary of the same name. They share their stories straight down the barrel of the camera, it’s very raw television, but it’s captivating and mesmerising. I’m very proud of that.

I think the exhibition pushes you to question yourself, your identity. It’s a big question for Australia because what does an Australian look like? It’s not just blonde-haired and blue-eyed. It’s Sri Lankan Tamil, it’s Lebanese, it’s Greek. It could be from all over the world. It’s people from mixed backgrounds and we should be proud of that. I just deeply want people to feel proud in their skin.

For students at ANU, some that do want to fight against racism, and others that may have witnessed racism and don’t know how to handle it, what would you say to them?

I really believe in calling it out. You can’t be a bystander, it’s not good enough. Silence is complicity. If you’re afraid and it’s a dangerous situation, you immediately call police or security. But if you hear someone racially vilifying someone else, you’ve got to call it out. It happened in Sydney recently, a bus driver was racially vilified and a young boy, around primary school age, went up to the bus driver and said “I’m sorry you were subjected to that.” He was supporting him and recognising that he’s a human being.

The final question is, what are your future plans as an ANU Fellow? What can students look forward to seeing from you?

Well that’s a very big question. For me, the future at the moment is all about inspiring ANU students, and motivating and working with them. The future is all about working with our youth, it’s about seeing and developing and working with them, seeing how far they can go with combating racism through our arts activism program and also mentoring students. I’m inspired seeing our ANU Master Class students going further with arts activism, being in the media, making a difference and taking charge.

I’m very excited about the present and the future. I’m excited about what we can create. It’s all about young people taking charge, and it’s a lot on their shoulders and I feel that’s a lot of pressure. But I think young people are more interested and engaged about using their voice. And I want to help give them that platform so they can be as effective as possible in creating change, in making a positive impact on society.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.