There is a movement building momentum all over the world, and that focuses on making it more common for nature to have legal rights. No, this does not mean that a tree will have the same rights as you – it merely means that some parts of nature will have more of a chance to stay protected than the current legal system allows.

In the 1970’s Christopher Stone stunned his half asleep property law class by proposing that nature have legal rights in some limited contexts. He wrote a book, Should Trees Have Standing? Which, at the time, made waves. He argued that, if non-living corporations can have legal personality, why can’t nature? It’s an opinion that is growing in popularity.

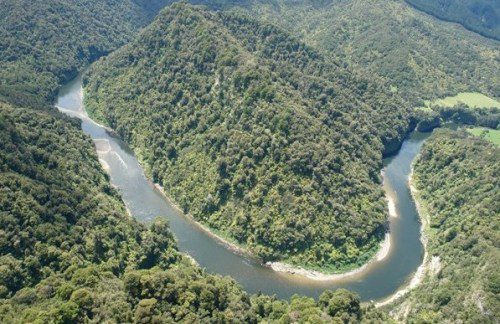

You might have seen that several rivers have been granted legal rights recently; one in New Zealand and another in India. Legislation and judicial rulings respectively provided each of the rivers with a set of rights which are enforced by specific guardians of the river – traditional owners of the land, who are able act on behalf of the river.

In both cases, multiculturalism and collaboration have been central pillars upon which the changes have occurred. As such, there is a massive link between the granting of legal rights and recognising the cultural ties traditional owners have with their land. In New Zealand, one guardian is an appointee from the New Zealand government, and one is a local Maori. This is beneficial to both the environment and culture in the nations that have been inventive enough to begin taking this legal movement seriously.

At present in Australia, natural objects do not exist in their own right before the law. For example, ‘damages awarded as a result of the pollution of a river are not necessarily applied to reinstate the river to its former unpolluted state.’ Similarly, if the river is being polluted it has no standing to challenge the pollutants actions: it must wait for a human to demonstrate the invasion of its rights.

This is unlikely to occur every time as environmental litigation is often undertaken by community groups with few funds in an expensive, inaccessible and complex court system.

As a result, there is a range of natural phenomena that really aren’t being protected by existing legal structures. It does not take long to find an example close to home – the Great Barrier Reef, a World Heritage Area and dumping ground for pollutants.

There are of course a lot of questions raised when one proposes large changes to the law. However, re-thinking how we approach environmental law is not a futile exercise, in my opinion.

In Queensland, the Northern Queensland Environmental Defenders Office began mounting a campaign in 2014 to allow the reef to have a legal personality and, therefore, ‘an independent right to seek justice before the relevant courts.’ This movement is in the preparation stage, but the plan is to draft a Bill, and submit a petition for a plebiscite to Parliament to see if there is sufficient support for this idea in Australia.

What this would do is allow for a body or panel of people to act as guardians of the reef, allowing them to enforce the reef’s rights when the need arises. While this idea may be conceptual, the discussion is worth having when one of the most unique pieces of our environment is continuously under threat.

This would be one of the first moves to grant legal rights to nature in Australia, with the only other tenuous example the Victorian Environmental Water Holder. It is a legal entity – a statutory corporation – set up to manage the rights of rivers in Victoria to increase efficiency and water recovery amidst a drought. This board is independent of the government, allowing for a greater prioritisation of the environmental integrity of rivers in the state.

This Water Holder was necessary, not just for nature’s rights, but for human water needs. It goes to show that our relationship with nature is continuously shifting, from resource reliance and exploitation to a recognition that humans and nature are interdependent.

Part of this might include a shift in our human-centric legal system – because not everything is about humans anymore when climate change is shifting the balance between us and the natural objects we have traditionally given little agency to.

I’m not going to pretend that this reform is perfect, or indeed that it ensures better protection than at present, but it is worth consideration. At the very least, we must re-evaluate our attitudes toward the environment, and we must reconsider how natural wonders like the Great Barrier Reef can be best protected.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.